The 20-Year Cycle (Part III)

This is Part III of a three-part series regarding the 20-year cycle in the stock market.

Part I of this series contained some "Bad News" and Part II contained some "Good News". Part III contains more bad news - that can potentially be twisted into good news. For a close examination of stock market performance on a repetitive 20-year basis reveals some months that are consistently poor performers. That's the bad news. The good news is that by avoiding these particular months an investor might be able to gain an "edge".

The 20-Year Pattern - Part III

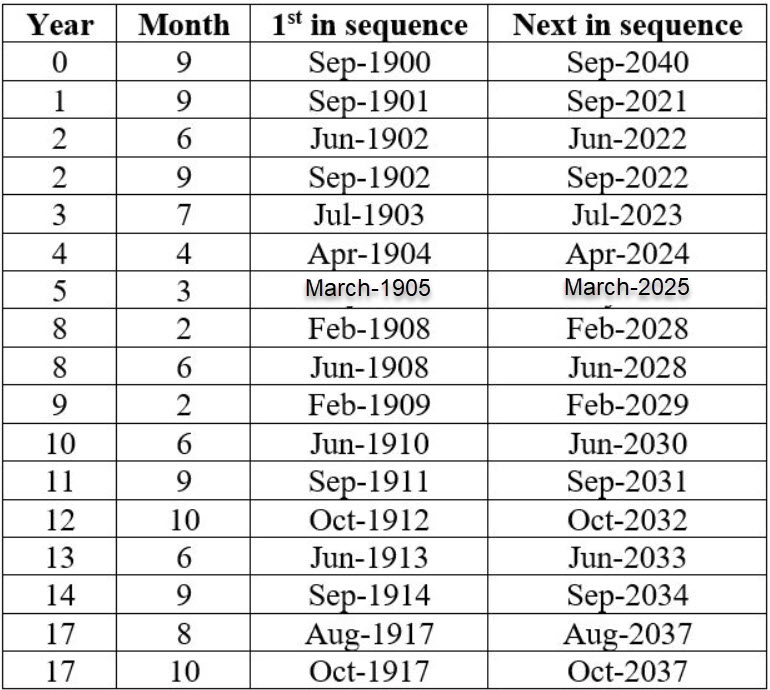

The months we will look at are what I refer to as the "Ugly 17". These are 17 months out of every 240 months (i.e., 20-year cycles starting in 1900) that have tended to witness poor stock market performance cycle after cycle.

For each purposes each 20-year cycle starts with "Year 0" (i.e., 1900, 1920, 1940, etc.) and ends with "Year 19" (i.e., 1919, 1939, 1959, etc.).

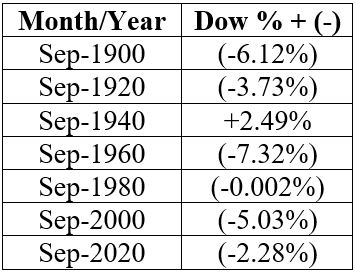

For openers let's consider just one example. The 1st month in the "Ugly 17" is "September of Year 0". The figure below displays the price change for the Dow Jones Industrials Average during that month in the past.

As you can see, every 20 years (starting in 1900) - with one exception (1940) - the month of September has come up a clinker. This represents only one of the "Ugly 17" months. The others are:

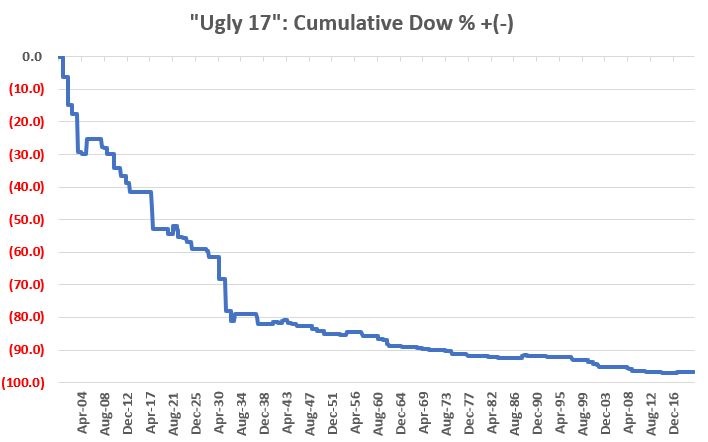

Now let's consider the performance of the Dow ONLY during these "Ugly 17" months as a whole. The chart below displays the cumulative % +(-) (with an emphasis on the minus sign) for the Dow Jones Industrial Average ONLY during these same 17 months during each 20-year cycle starting in 1920.

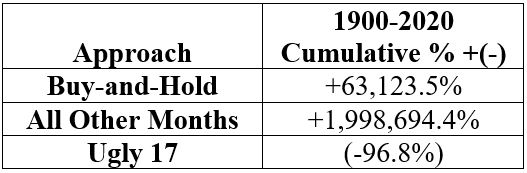

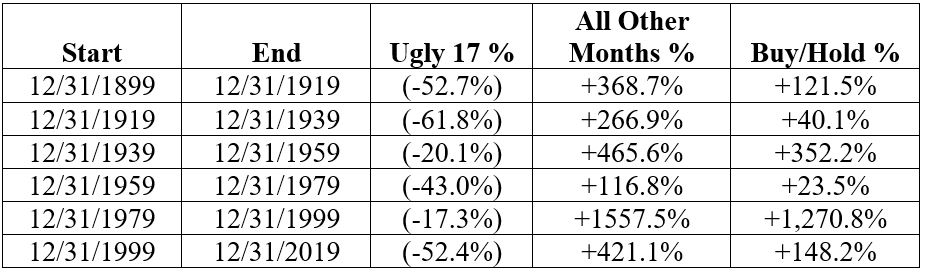

To get an idea, the table below displays the cumulative % +(-) across each 20-year cycle for:

- Ugly 17 Months ONLY

- All Other Months ONLY

- Buy-and-Hold

So, what's the "Good News" in the "Ugly 17"? By avoiding these 17 months each 20-year cycle (for our test purposes we assume a 0% return during the "Ugly 17" months and a return equal to the percent price change for the Dow Jones Industrial Average during all other months), an investor might have vastly outperformed a buy-and-hold approach.

Summary

So can an investor simply "follow the calendar" and outperform buy-and-hold by a significant sum. Well, maybe. The results above are fairly compelling, particularly since they rely on the exact same set of months on a repetitive 20-year basis. Still, as I always say, relying on any type of seasonality requires something of a leap of faith, as there is never any guarantee that what worked last time around will work again this time around.