Fundamental Overview: Part 1

This is Part 1 of a weekly update on the U.S. stock market's long term fundamentals. This part is rarely updated. Part 2 is updated each week.

Here's how I approach the fundamentals of a country's stock market, such as the U.S. stock market. The key to fundamentals is to think about stocks not as pieces of paper to be bought and sold, but as part ownership in a business that generates earnings. Or as Warren Buffett says:

- In the short run the stock market is a voting machine.

- In the long run the stock market is a weighing machine.

20+ year basis

Traders often ask "what can push the stock market up?" In my opinion, this is the wrong question to ask. The correct question is "what can push the stock market down?". In the absence of a solid reason for the stock market to go down on a multi-year basis, the stock market's natural bias is to go up. Why? Because the majority of people live their lives trying to make each day better than the last. If stocks are part ownership in businesses, then the broad stock market tends to go up on a 20+ year basis because the majority of businesses seek to make more money tomorrow than they did yesterday. If you look at a multi-thousand year history of mankind...

Belief #1: long term optimism triumphs over long term pessimism.

*It's also important to remember that the modern era is much more stable than centuries past. This is partially why global economic growth was snail slow and had massive crashes up until the Industrial Revolution. E.g. today we have few global phenomenons that significantly destroy major economies (imagine Genghis Khan's destruction across Asia, the Black Plague which destroyed 1/4-1/3 of the population, WWII, Communist Revolution in China, etc).

Belief #2: 3 things that PERMANENTLY drive a nation's stock market on a 20+ year basis.

If the stock market is a weighing machine on a 20+ year basis, then 3 main SUSTAINABLE factors drive a stock market's earnings on a 20+ year basis. Other things - such as increases in profit margins and increases in valuation - cannot be sustained forever. E.g. profit margins cannot go from 10% to 30% to 60% to 90% to 120% over 50 years. There is a limit.

To put it simply, in order for a nation's public corporate sector to earn more profits, it must earn more profits at home or abroad.

Increase in DOMESTIC earnings:

- Increase corporate earnings per capita. This applies moreso for developing countries whose GDP per capita can grow more rapidly because there is a lot of room to "catch up" to developed countries.

- Increase in population (increase in "capita"). If corporate earnings per capita (like GDP per capita) are stagnant but the population increases, then corporate earnings as a whole will increase.

Increase in FOREIGN (international) earnings:

- Increase in foreign competitiveness and international appeal. A nation's corporations (e.g. Publicly-listed Corporate America) can earn more money not just at home, but also abroad. Keep in mind that the international landscape is ever-changing. This change causes certain country's companies' products to be more/less desirable overtime. For example, Chinese companies' international appeal has increased over the past 2 decades, whereas Japanese companies' international appeal has been virtually stagnant over the past 2 decades. The following table compares China's vs. Japan's exports in USD. You can also "feel" this intuitively. Do Japanese companies (e.g. Toyota, Sony, Toshiba) have the same global footprint they had 20 years ago?

There are 2 main ways for a business to be successful:

- The business can enter a brand new market (major innovation)

- The business can enter an existing market and compete on price (low-cost) and/or small scale improvements (e.g. small innovation)

The same concept applies to a nation's publicly-listed corporate sector. Afterall, what is a nation's publicly-listed corporate sector but a collection of businesses whose goal is to make profits?

How I see the U.S. stock market today

On a 20+ year basis, I am bullish on the U.S.. On a 20+ year basis, all we need to do is make sure the U.S. isn't in a Japanese-like situation. For the U.S.:

- Aggregate corporate earnings per capita: hard to grow rapidly since the U.S. is not a developing nation like China. However, corporate earnings per capita is unlikely to decline on a 20+ year basis, unless the U.S.' productivity per worker permanently and drastically decreases. This seems extremely unlikely.

- Increase in population: The U.S.' population is still increasing, unlike other developed countries like Japan. A more ideal scenario is that of Australia, who's population growth is one of the highest among developed countries.

- Increase in foreign competitiveness and international appeal: I think publicly-listed U.S. companies will continue to earn more and more from ex-U.S. sources. Using our previous analogy, the U.S. competes internationally on "major innovation". No other country comes close to the U.S. in terms of innovation.

The reason I'm optimistic about the U.S. and not Japan is because Japan fits the above mold in a less positive manner.

- Like the U.S., Japan is a developed country. Hence, growth in corporate earnings per capita is slow.

- Unlike the U.S., Japan's population is virtually stagnant (and is projected to decline).

- Unlike the U.S., Japanese companies as an aggregate don't have significant growing international appeal. Japanese companies are caught between 2 forces. Japan isn't at the high end of the global value chain, where the U.S. is the #1 innovator. On the otherhand, Japan isn't on the lower end of the global value chain, in which China dominates and is moving up the value chain. In short, Japan is squeezed in the middle. I don't think it's a coincidence that China's rise coincided with Japan's secular stagnation.

*Culture also plays an important role (even though no one likes to discuss culture in a PC world). Asian culture focuses more on repitition (e.g. copying) and improving, whereas western culture (in particular U.S. culture) focuses more on thinking outside of the box and innovating. This stems from different education systems in Asian vs. western countries. This is useful for small scale improvements and innovations, but is not ideal for the mass creation of major groundbreaking innovations.

*Like everything else, population and immigration trends are subject to change. For example, the U.S. is turning increasingly strict on immigration, while Japan is trying to open itself up to immigration. While these actions may impact population trends, it's too early to say. In general, I try not to avoid long term predictions as much as possible.

*These aren't the only factors that impact a nation's stock market's 20+ year outlook. However, I believe these to be the main ones. Separate the signal from the noise. Essentially, we're just asking one question:

- Will the country's stock market go up a on 20+ year basis? Or will the country be like Japan?

That's the one and only question I ask myself on a 20+ year basis. I don't try to predict the rate of long term GDP growth, productivity growth, inflation, debt levels, etc. Plenty of very intelligent people have spent a lifetime trying to predict these things, and their predictions are usually no better than a 50/50 coin toss. I am not smarter than these people. Know your limit.

5-15 year basis

As Warren Buffett says, a good business can be a poor investment if bought at the wrong price. The same thing applies to a nation's stock market, which is really just a collection of businesses. Valuations are extremely important on a 5-15 year basis. Here's an example.

Assume you own a business. This business's price is $100 and earns a guaranteed $5 per year (after adjusting for inflation). What is your rate-of-return if you buy this business? 5%, which is the earnings yield. The earnings yield is the inverse of forward P/E. As you can see, the earnings yield determines your returns over the next 5-15 years.

Now of course this assumption is nonsensical because the business will not earn a GUARANTEED $5 per year. This isn't a risk-free bond that you hold until maturity.

However, the S&P 500's inflation-adjusted earnings are rather stable on a 15 year basis. Sure, there are spectacular crashes and spectacular surges on a YoY basis. But on a 15 year basis, earnings tend to be rather stable. From 1900-present, the S&P 500's inflation-adjusted earnings have grown an average of 1.8% per year.

Since corporate earnings tend to grow rather slowly, the main factor that impacts the stock market's 5-15 year outlook is its inflation-adjusted earnings yield. From 1900-present, the S&P's average inflation-adjusted earnings yield (trailing 12 months) has been 7.42%. This is the main reason why the stock market returns an average of 7-8% per year from 1900-present, after adjusting for inflation. Much smaller factors include a long term increase in valuations (i.e. average valuations in the early 1900s were lower than valuations over the past 10-25 years).

*Many investors can recite the fact that the S&P returns approximately 10-11% per year on a multi-decade period (7-8%). But knowing WHY is important, because this may not hold true in the future. 7-8% real is not engraved in stone. Perhaps the next 50 years will see lower long term returns IF valuations are consistently higher than they were in the past.

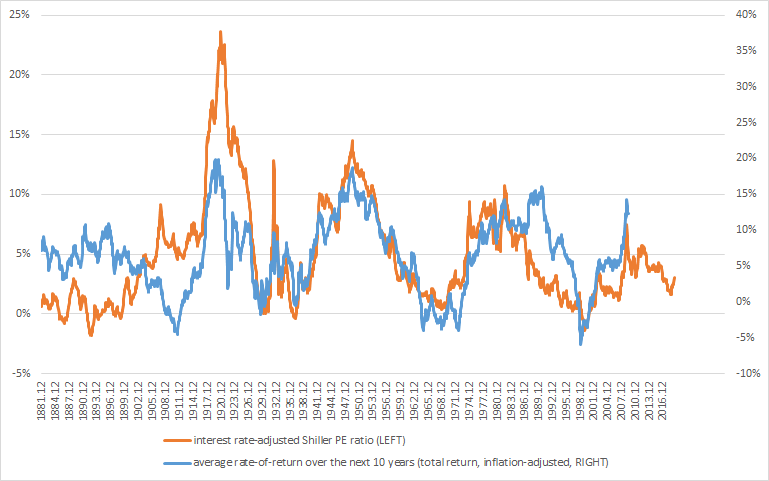

Looking at the above chart, we can see some key turning points:

- By the late-1940s, the S&P's earnings yield was high. The S&P surged over the next 10-20 years.

- By the 1960s, the S&P's earnings yield was somewhat low. The S&P did not do too well in the 2nd half of the 1960s and 1970s.

- By the late 1970s and early 1980s, the S&P's earnings yield was high. The S&P soared in the 1980s and 1990s.

- By the mid/late-1990s, the S&P's earnings yield was very low. The S&P did not do well in the 2000s.

From the above chart you can see that valuations (the inverse of earnings yield) have been consistently lower post-1995 than pre-1995. A significant part of this is the long downtrend in interest rates.

Various assets compete against one another for investors' money. So when interest rates are consistently lower than they were in the past, more and more investors go into equities in a "hunt for yield" (almost like arbitrage). In doing so, they push up equity prices, thereby consistently bringing down earnings yields compared to where they were in the past.

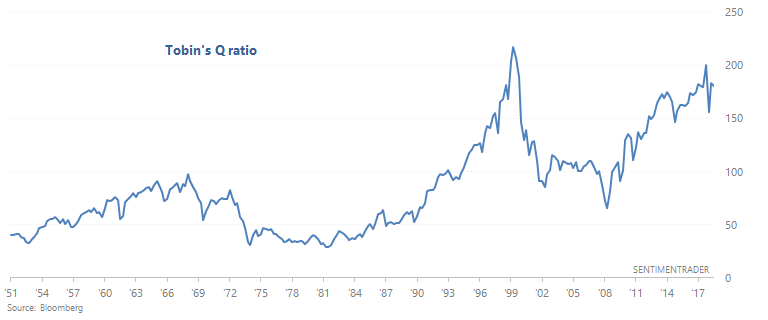

Regardless of which valuation indicator you look at, the U.S. stock market's valuations are high right now. This suggests that the stock market's inflation-adjusted returns over the next 5-15 years will be worse than average.

Here's the popular Shiller P/E ratio:

Here's the popular Tobin's Q:

1-3 year basis

Some investors and traders state that "the economy is not the stock market". I used to say that "the economy and the stock market move in the same direction in the long run". Both of these are somewhat correct, and somewhat incorrect.

- The economy drives corporate earnings, which drives the stock market on a 1-3 year basis.

- The stock market IS the economy IF every single business (include sole proprietorships and private businesses) is listed on the stock market. This is inherently logical. If a stock market index accounts for every single business activity in a country, then the stock market IS the economy.

- If the country's stock market roughly and proportionally represents its economy, then the stock market's earnings and the country's economy will move in the same direction in the long term.

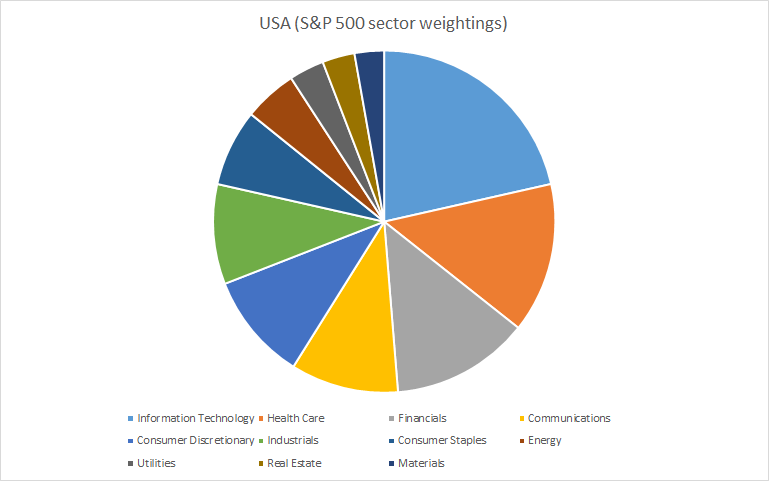

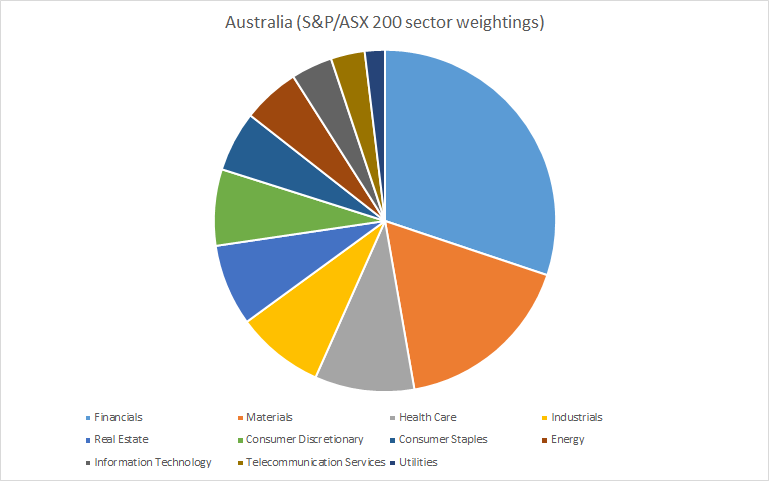

- This is more true in the U.S. than many countries. For example, countries that are smaller or are major commodities exporters tend to have an over-representation of certain industries in their stock market. (E.g. see the sector weightings below for the U.S. vs Australia, and you can see how the U.S. is more diversified.)

- *In countries whose stock market focuses more on 1 sector, if that sector does much better than the broad economy (for sector-specific reasons), then the country's stock market will do better than the economy. If that sector does much worse than the broad economy (for sector-specific reasons), then the country's stock market will do worse than the economy.

- In most cases, a country's stock market is fairly representative of its economy. Hence, for most countries the economy drives corporate earnings, which drives the stock market on a 1-3 year basis. For a good understanding of fundamentals, I suggest you read Ed Yardeni's autobiography.

About the U.S.

- Approximately 71% of the S&P 500's revenues come from domestic sources.

- As the biggest economy in the world (and by far the biggest stock market, at >40% of global stock market capitalization), the U.S. has an interesting phenomenon. When other countries experience a recession or stock market crash, the reaction if usually muted in the U.S.. But when the U.S. experiences a recession or stock market crash, the effects are felt in most parts of the world. This is why it's better to focus on U.S. economic data instead of foreign economic data when investing in the U.S. stock market. In order for U.S. corporate earnings and the global economy to really fall off a cliff, the weakness must show up in U.S. economic data.

*Keep in mind that the economy is an extremely complicated subject. No one has a perfect grasp of it. We are all like the blind men & the elephant - trying to grasp some partial truth about the economy.

In Part 2 of my Fundamental Overview I will examine the stock market's fundamentals on a 1-3 year time frame. This will be updated each week, and can be found on Premium Notes. If you have questions/comments, please email me at [email protected]