A new record in severely overvalued companies

Sentiment and valuation go hand-in-hand. One impacts the other and creates a self-reinforcing loop until something happens to break the cycle.

With some measures showing extreme or even record levels of optimism, it's not a big surprise that most measures of valuation are showing the same. About the only ones that don't are using the prevailing level of interest rates as a buffer, which may or may not be valid depending on one's worldview.

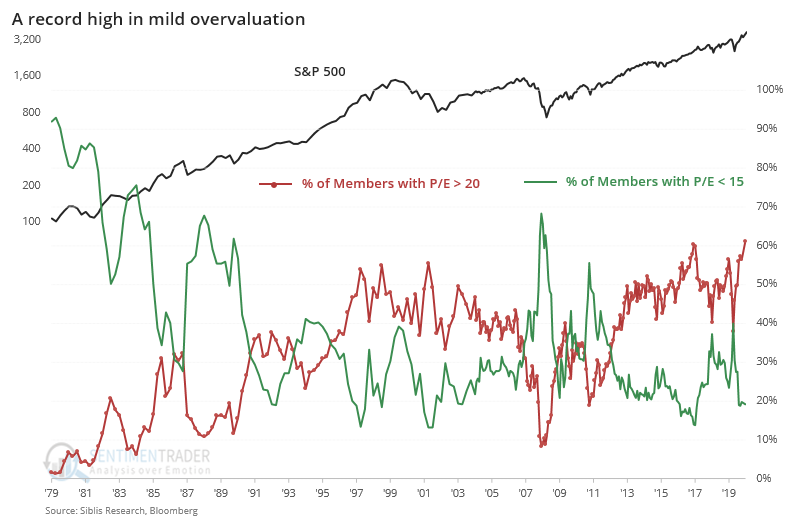

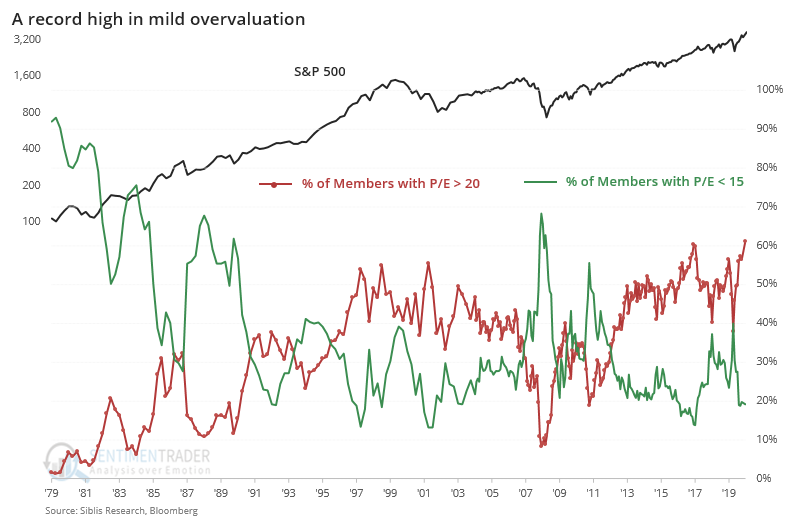

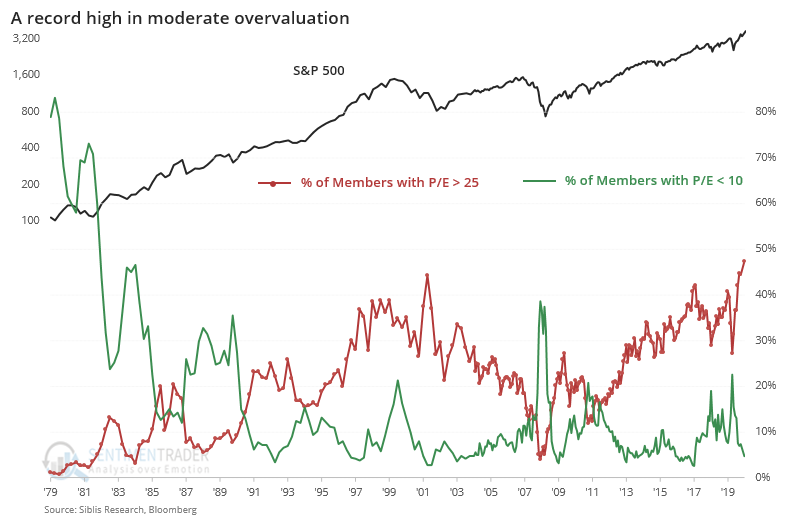

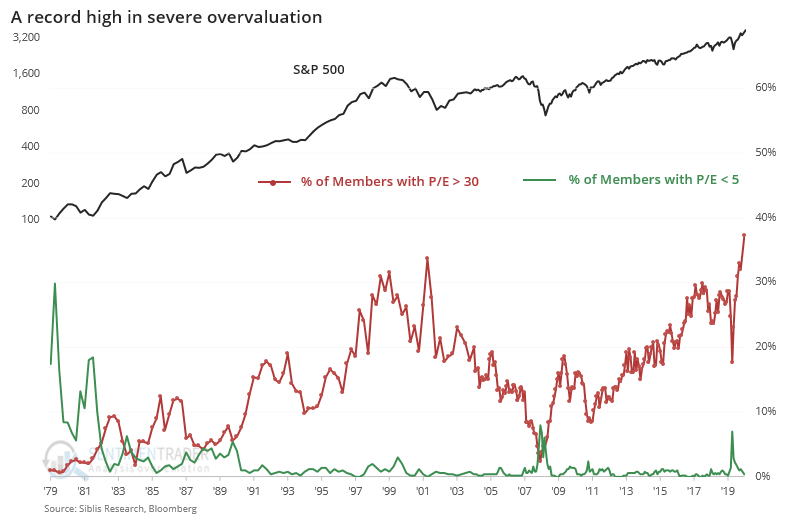

There can be little doubt that regardless of rates or future prospects, investors are willing to pay a high amount for current earnings. Over the past 40 years, there have never been more mild, moderate, or severely overvalued companies within the S&P 500.

Based on the latest data, we just surpassed the prior peak from 2017 with more than 60% of companies sporting at least a mild overvaluation, defined subjectively as having a price/earnings ratio above 20. This is using component stocks at the time they were in the index, not current members except for the last reading, so there is no survivorship bias in the data.

It's even starker when we look at the next step, moderate overvaluations, with a P/E ratio above 25.

When we focus on severe valuations, with a P/E above 30, there has never been anything like what we're seeing now. Nearly 40% of companies are currently sporting a valuation that high, and that's excluding the many companies that currently have negative earnings.

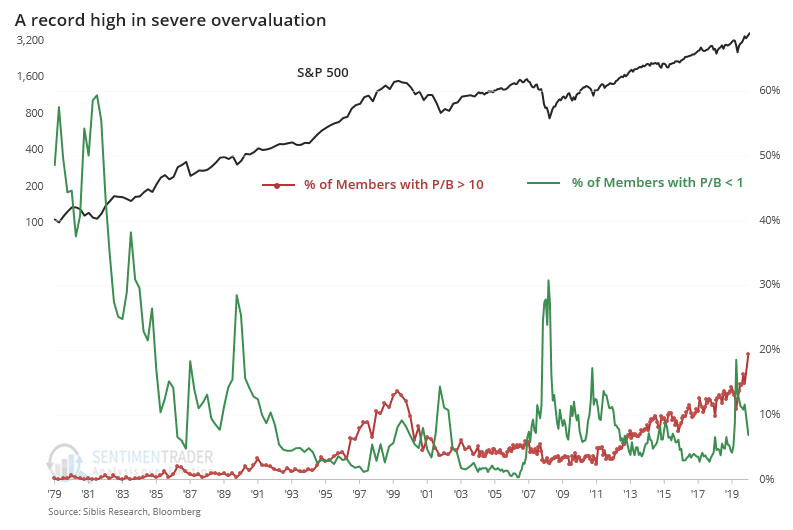

It's not just earnings. The same goes for using price/book value, with 20% of stocks having a ratio above 10, well above the prior peak in 2000.

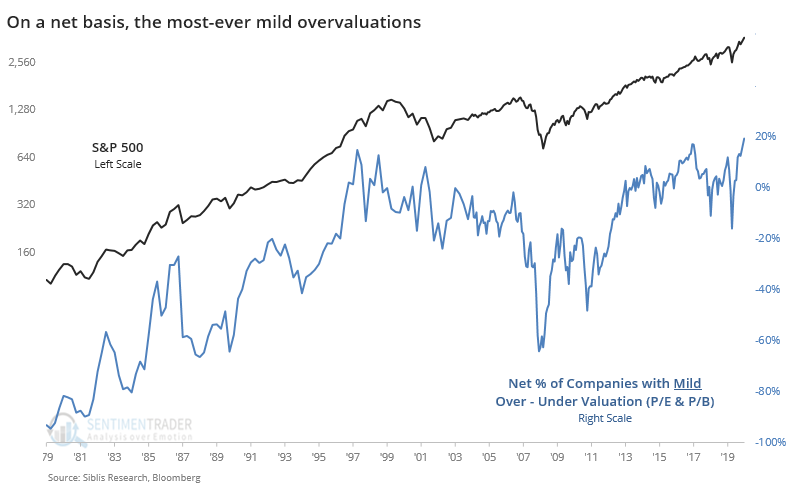

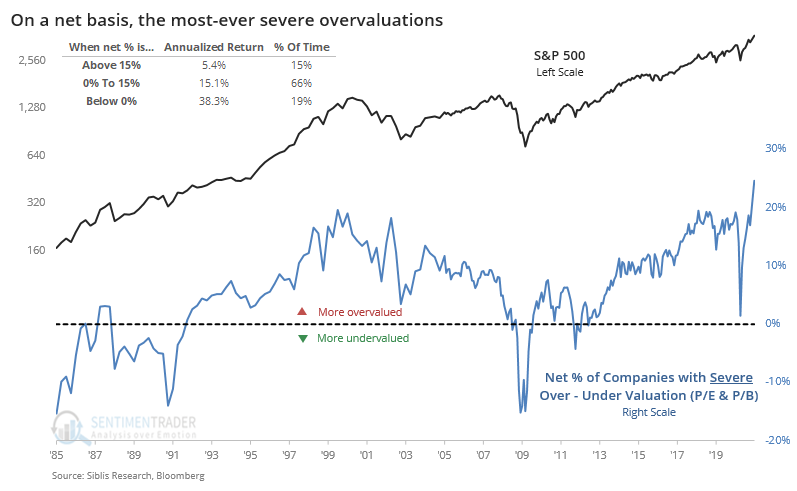

It's easier to see relative extremes when we use a spread instead. The chart below shows the percentage of companies in the S&P that had a mild overvaluation minus the percentage with a mild undervaluation, combining both price/earnings and price/book values. It just hit a record high.

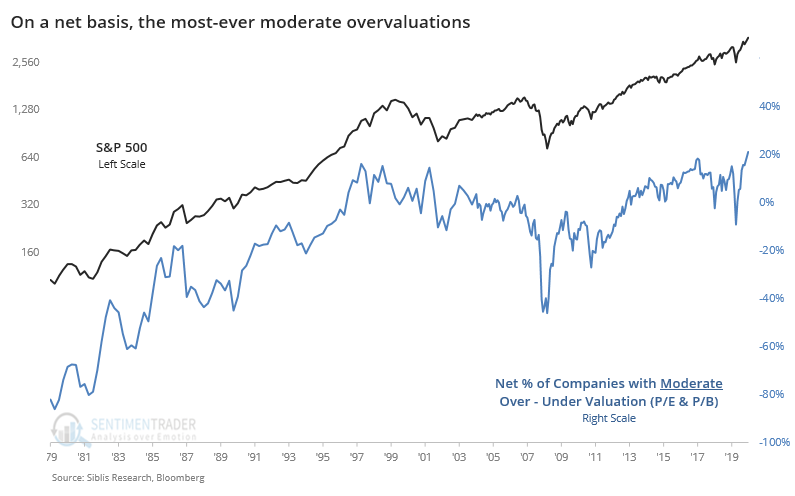

It's the same when we look at the net percentage of moderate valuations.

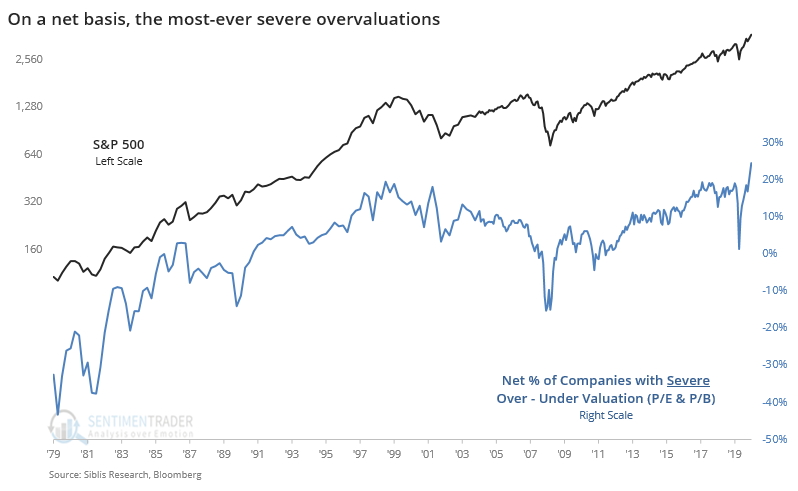

And the net percentage of severe valuations has likewise spiked after almost reverting to neutral territory earlier this year.

The late 1970s through early '80s was dominated by a period of severe undervaluation, so if we start our time frame in 1985, then we can more clearly see the recent extremes. The surge in 2020 is remarkable.

The chart shows a big difference in annualized returns depending on how many stocks were over- versus under-valued, with weaker returns when there are more overvalued companies. That should surprise exactly nobody.

Investors are currently pricing in a major rebound in economic activity and earnings potential in 2021, which Wall Street is already anticipating. A big rebound in earnings will alleviate some of these extremes, but it's unlikely to be enough to push most of these severely overvalued companies even to moderate or mild overvaluation. This is a major concern.