A banner year for returns versus volatility

Key points:

- The S&P 500's return over the past year is now 50x the volatility of its daily returns

- That's nearing a historic extreme, as it is for the Nasdaq 100

- Such years can generate complacency, but they have not necessarily been a boon for knee-jerk contrarians

A banner year

It's been a banner year for equity investors - historic, among the best ever - and maybe that's a problem.

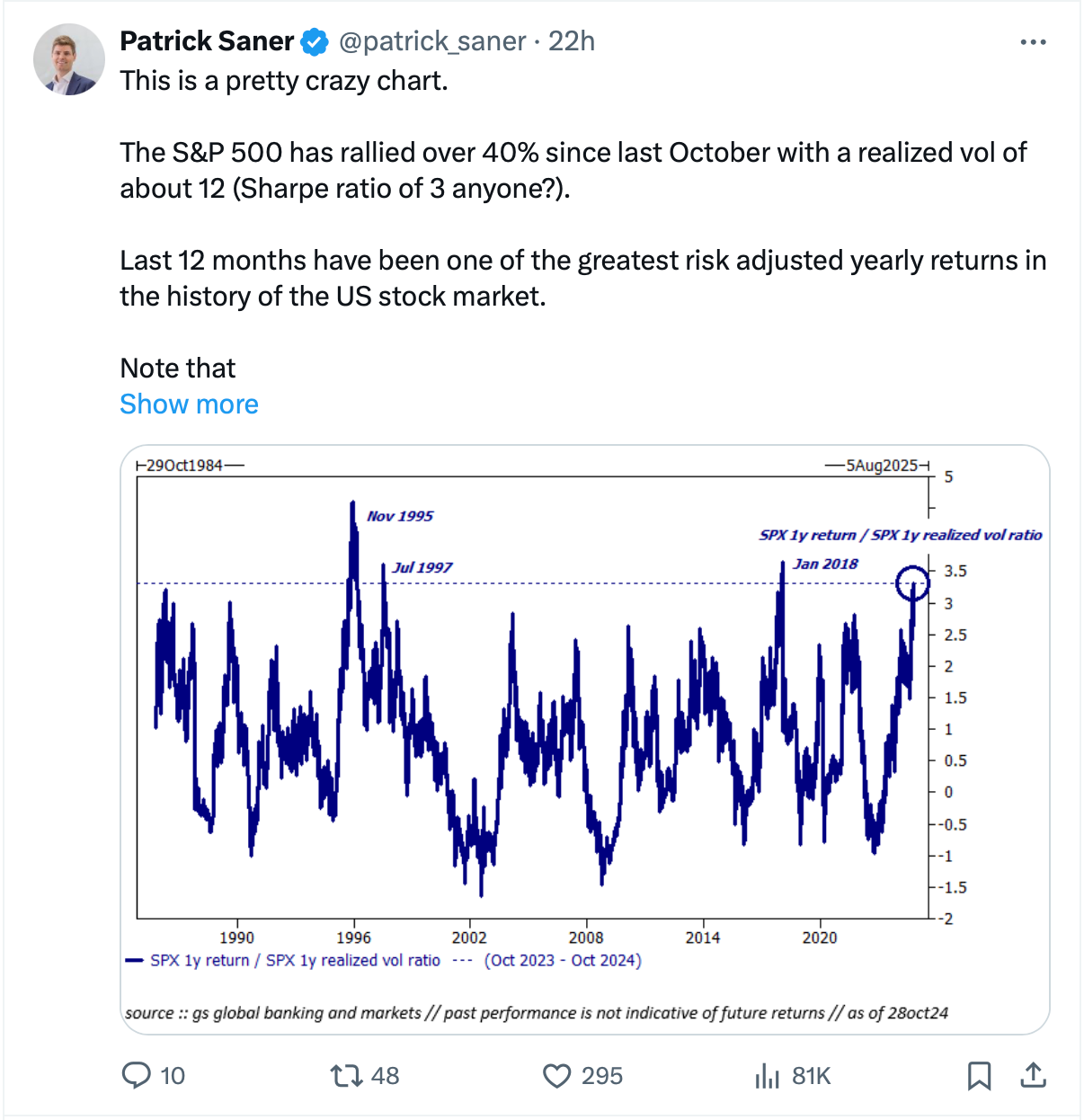

Patrick Saner from Swiss Re published a post on X about a phenomenon we've discussed in the past, an extreme jump in stocks' returns per unit of risk.

He's undoubtedly correct. We've used essentially the same methodology to compare trend and volatility before, like in July 2021. It's time to revisit.

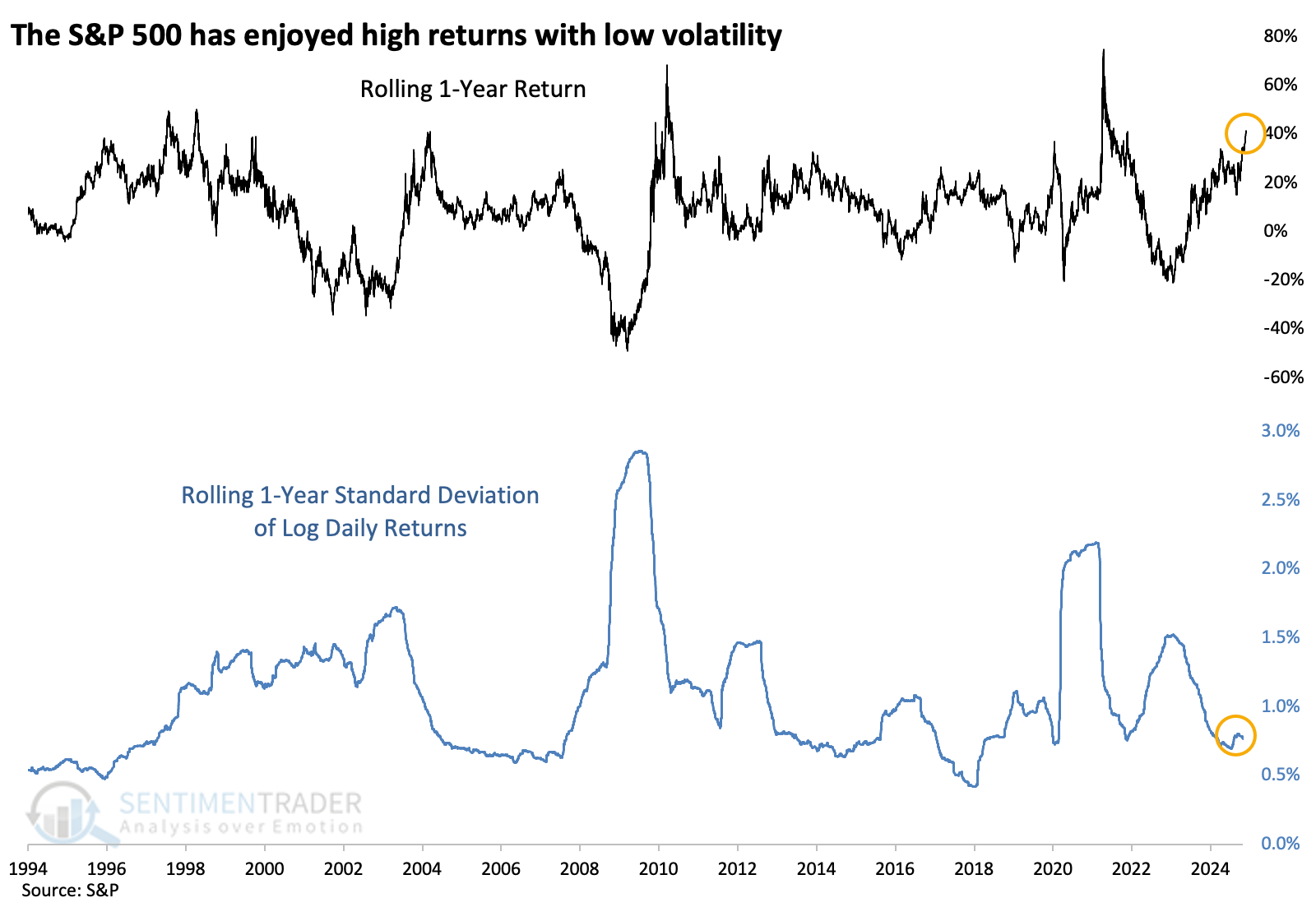

Below, we can see the S&P 500's rolling one-year return along with the standard deviation of a log of its daily percentage return. The two series are at opposite ends of the spectrum - returns are soaring, and volatility is stagnant.

When we divide returns by volatility, we can get a sense of how pleasant (or not) the environment has been for investors. And it's been very, very pleasant, the best of all possible worlds.

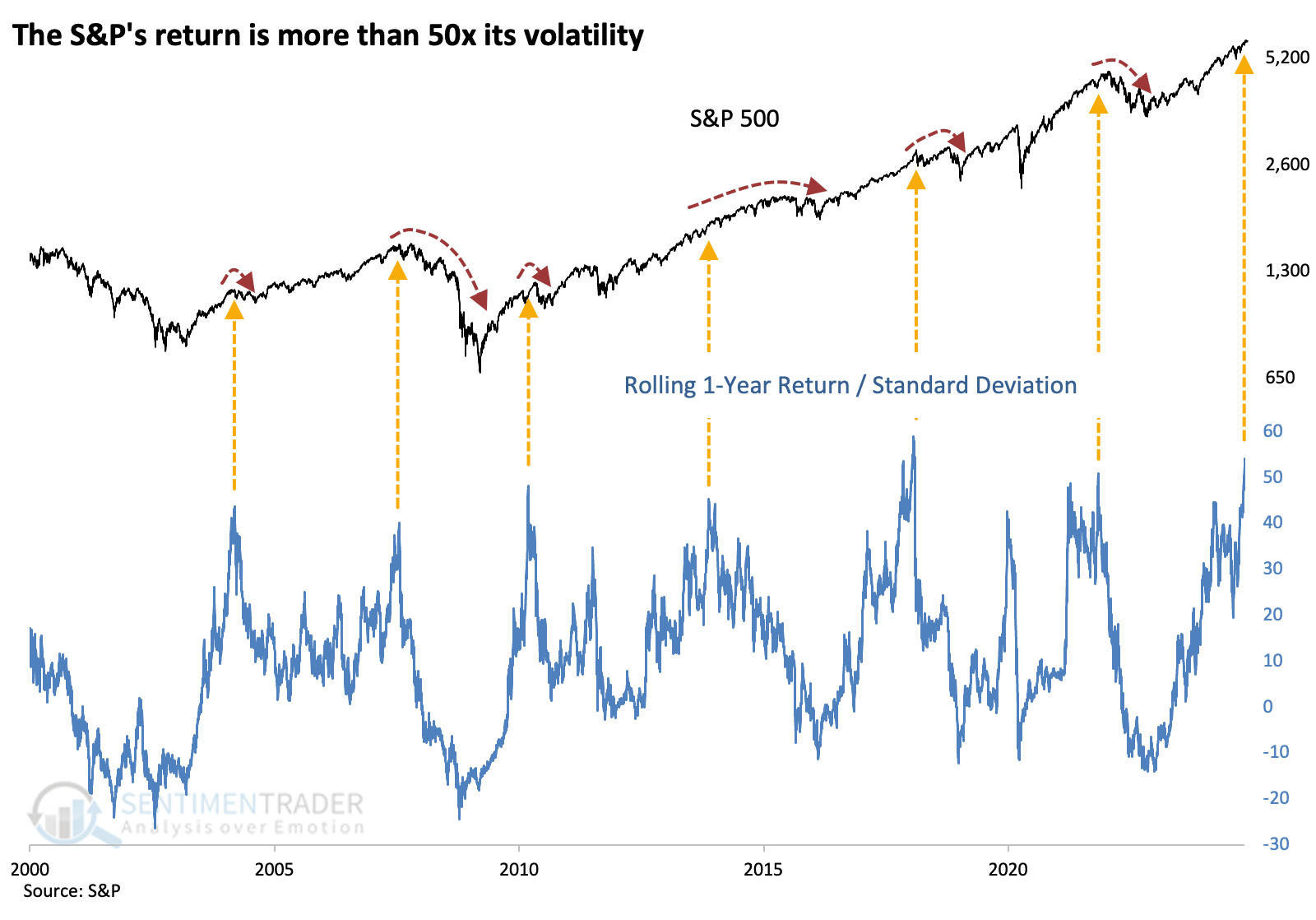

The S&P 500's rolling one-year return just exceeded 50x the standard deviation of daily returns, the 2nd-highest in 25 years. Unfortunately, the pleasant conditions haven't persisted for much longer over that span. For everything there is a season.

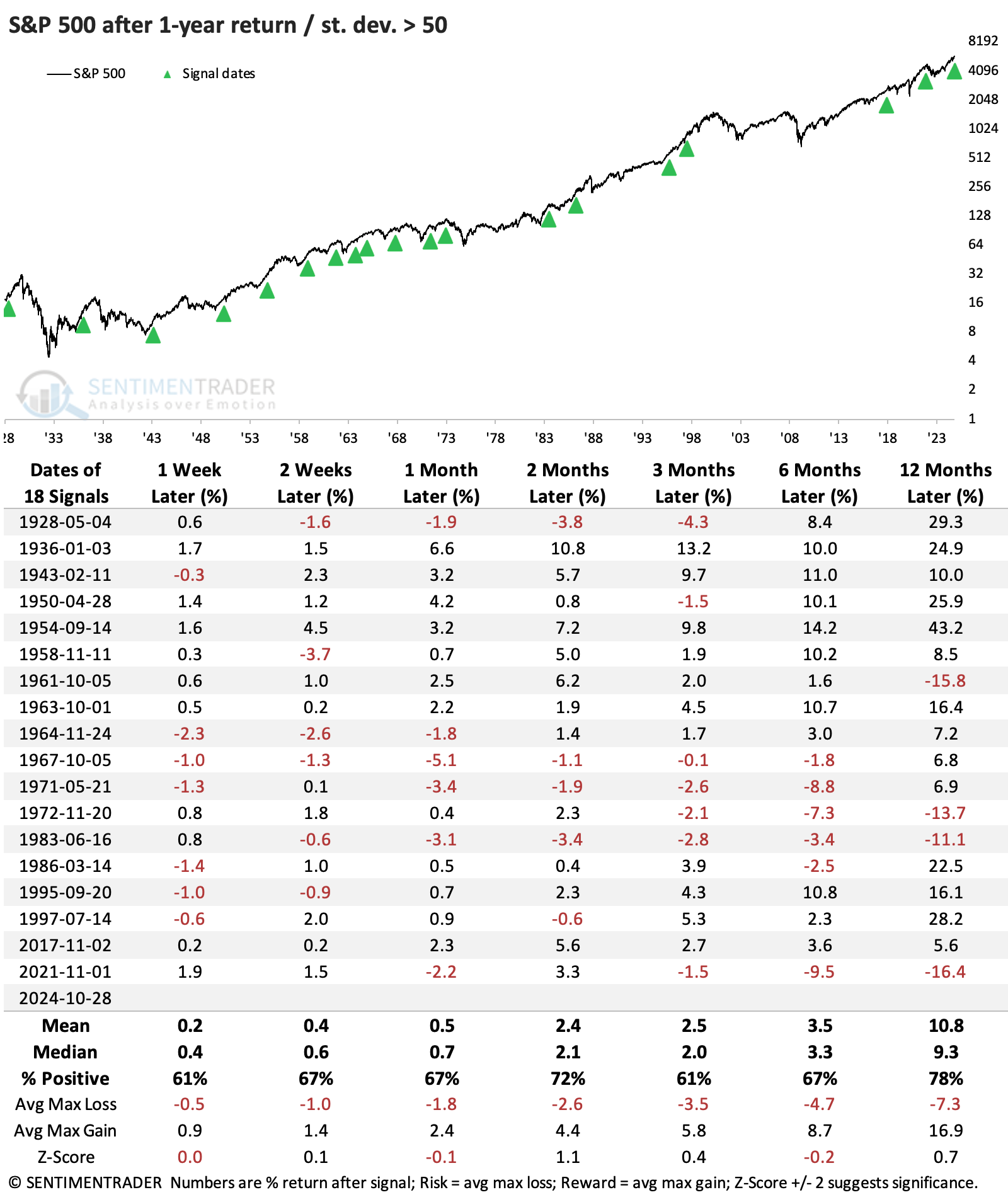

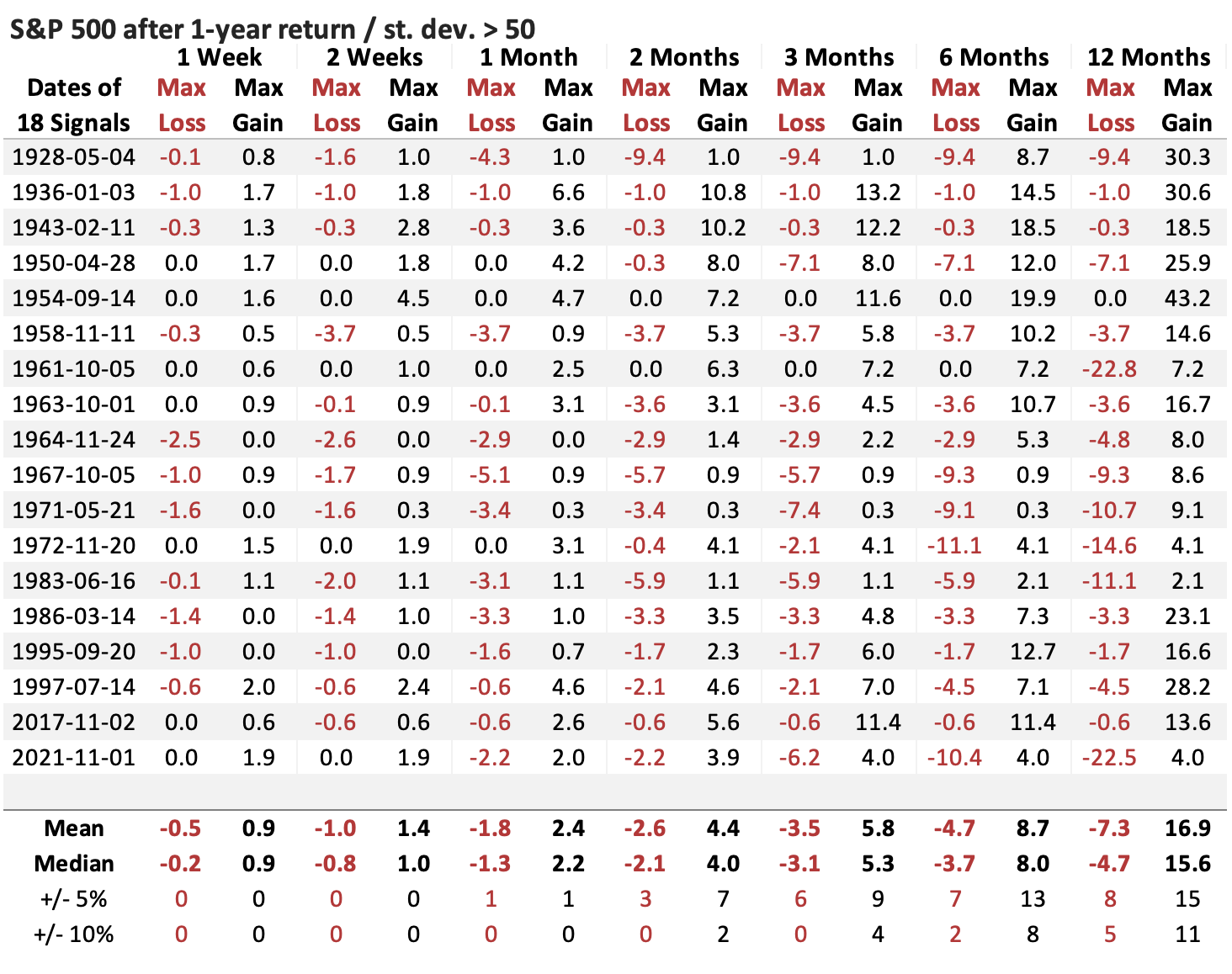

Going back further and looking at the most extreme cases, we see the S&P's returns after its rolling one-year returns first exceeded 50x its standard deviation.

There isn't anything particularly notable about the forward returns, with a mixed win rate, modest returns, and a tepid ratio of reward to risk. The signals were mostly great before the 1970s, mostly terrible during that decade (roughly), and mixed since then, especially over medium-term time frames.

The table of maximum gains and losses across time frames shows that the skew was mostly toward moderate gains versus losses (+/- 5%) and more heavily skewed toward significant gains (+/- 10%). But most of those were in earlier decades, with the skew much more balanced since the 1960s. Since then, over the following three months, there were four drawdowns larger than -5% and four drawups larger than +5%. A toss-up.

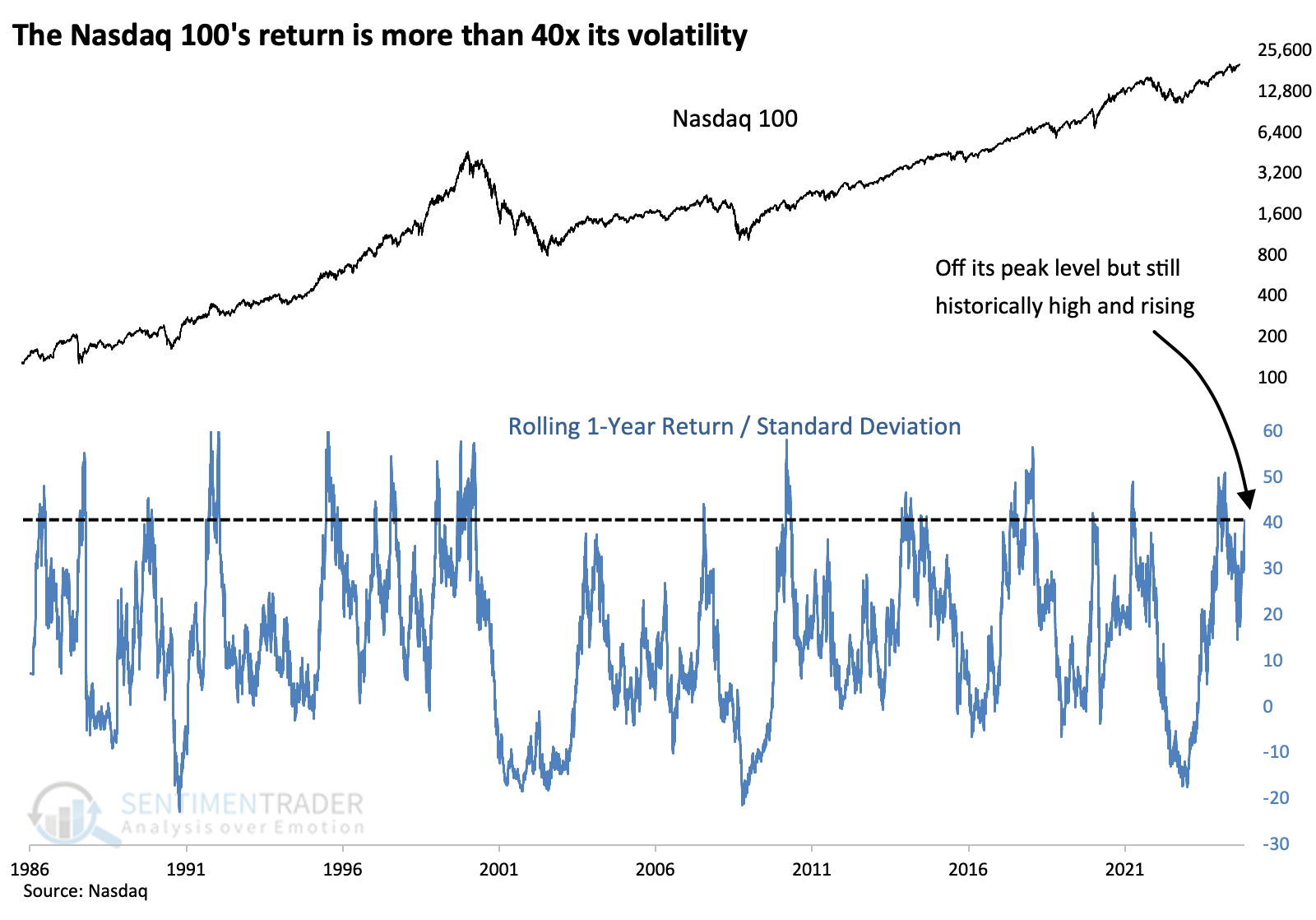

The S&P isn't alone

While it might seem like the relentless rise of the big tech trade should make the return/volatility ratio even more extreme than on the S&P 500, it wasn't the case. The Nasdaq 100 is generally more volatile, so while its returns have been impressive, investors have suffered more volatility in the process.

Even so, its ratio is back above 40x, high enough to be considered historically extreme.

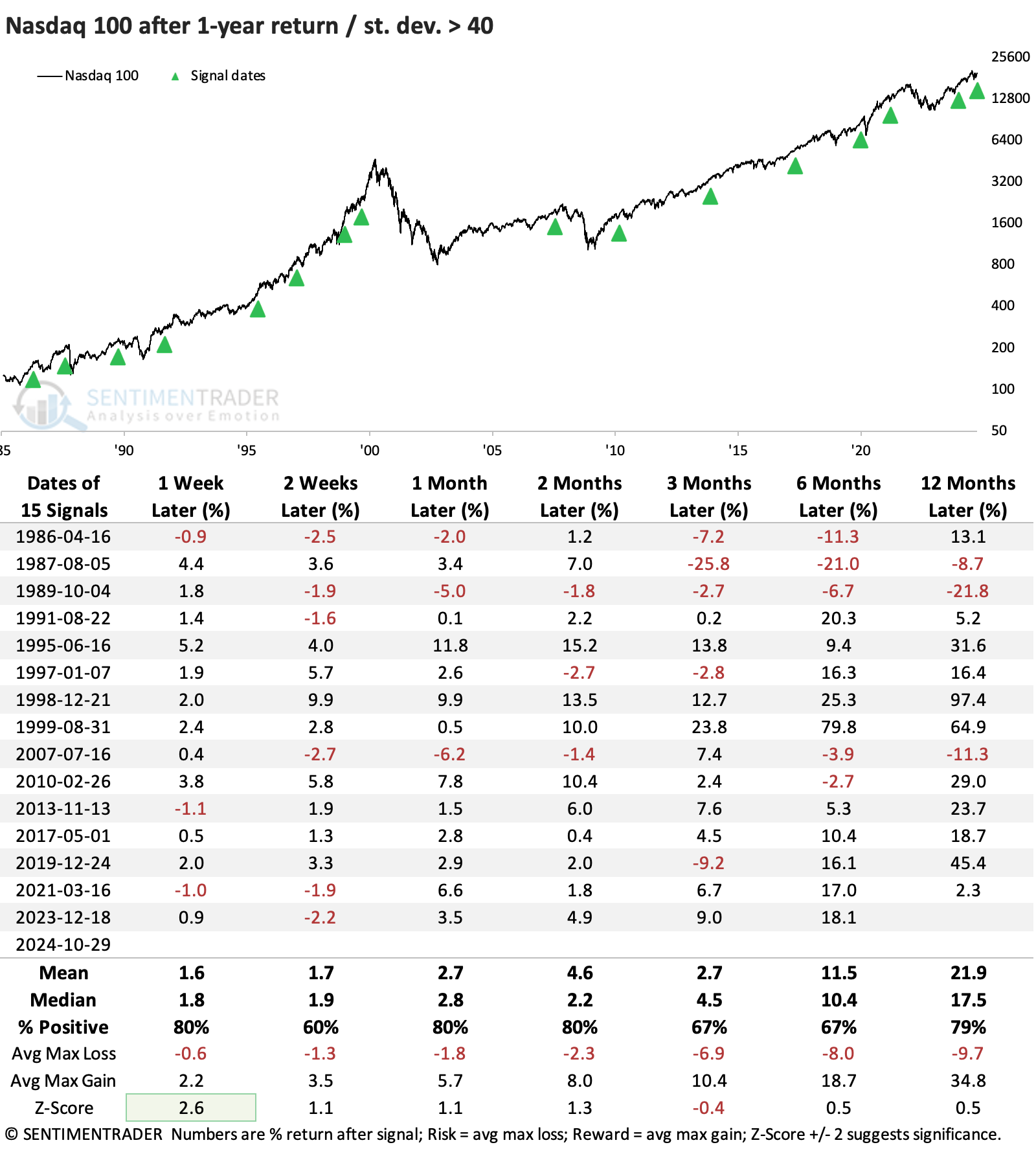

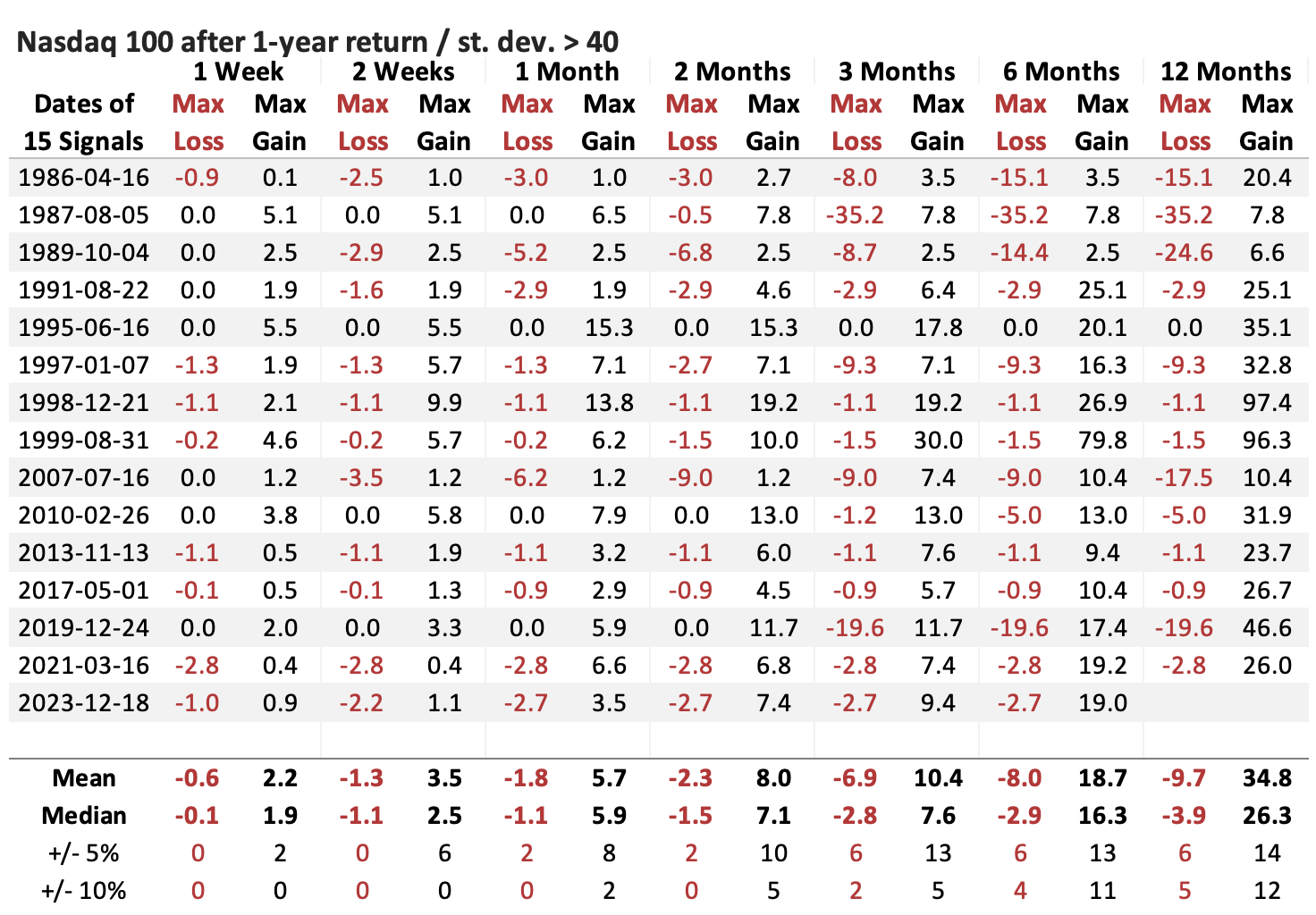

These extremes tended to be more of a positive sign for tech. Over the next 1-2 months, the Nasdaq 100 (NDX) rose 80% of the time. Over the past 30 years, the NDX declined over the next month only once. Since the 2008 financial crisis, the signals have preceded mostly positive returns, but over the next couple of months, they were pretty tepid.

The NDX's table of max gains and losses across time frames shows a bit more positive skew than the one for the S&P. Within the following three months, the NDX rallied at least +5% more than twice as often as it declined more than -5%.

What the research tells us...

When the environment is easy sailing, as we've witnessed over the past year, investors look for an excuse to reduce exposure and protect gains. There is no doubt that for the S&P 500, in particular, the past year has been as near to nirvana as we're ever likely to see, and that's worrying for contrarians.

The problem for those contrarians is that selling based solely on the easy gains has usually been a mistake. The S&P never fell into a correction within the next three months, while it added to its gains by double-digits several times. That can generate a lot of regret. But regret is a very personal thing, and there is something to be said for sleeping restfully, with gains on hand, rather than fretting about overnight risks. Recent history has been less kind to complacency, and for those looking to sleep better, it provides some evidence that letting easy gains ride is sometimes a risky endeavor.