The S&P's Inflation Adjusted Yield Just Plunged to a Record Low

Whatever one thinks about the outlook for inflation, it's hard to debate the idea that it's already here. Using traditional ways of measurement, virtually all of them are high and rising.

Until recently, one of the main arguments for stocks was that even though they weren't yielding much, at least they were earning more than Treasuries, even after accounting for inflation.

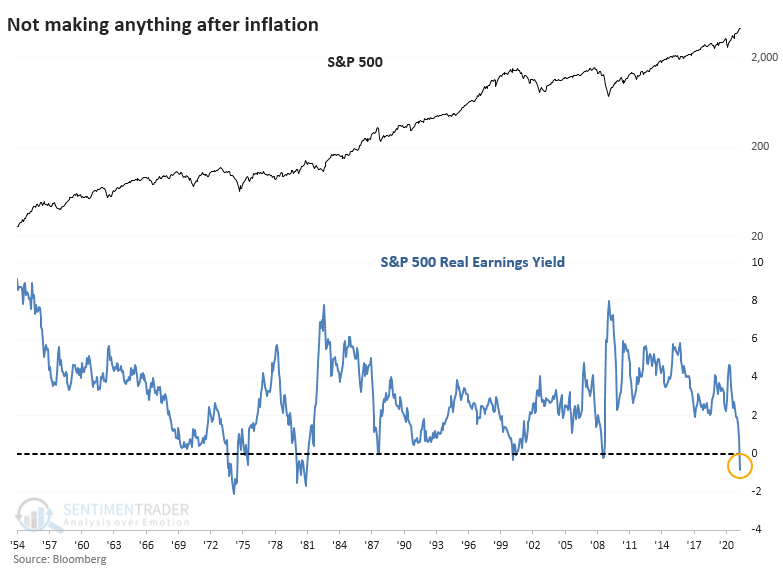

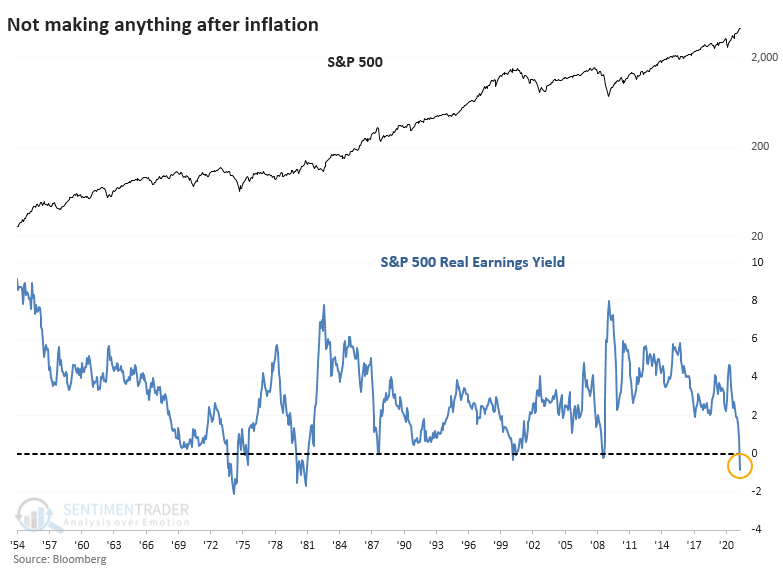

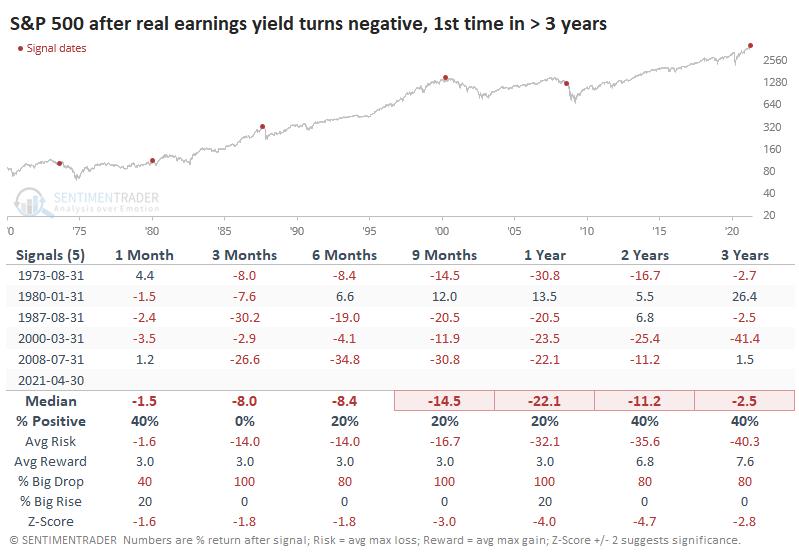

Now that there has been a spike in inflation gauges, the earnings yield on the S&P 500 has turned negative. This is not a condition that investors have had to tackle much over the past 70 years.

When an investor in the S&P adds up her dividend check and share of earnings, then subtracts the loss of purchasing power from inflation, she's barely coming out even. This is a record low, dating back to 1970, just eclipsing the prior low from March 2000.

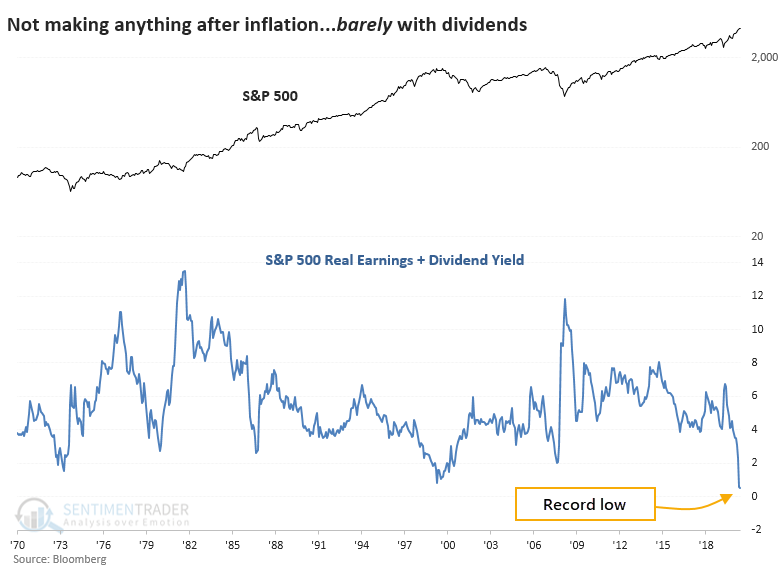

NEGATIVE REAL YIELDS = TROUBLE

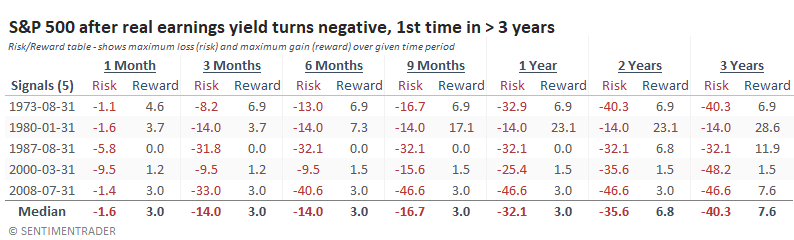

If we ignore dividends, then there have been five other times when the S&P 500's inflation-adjusted earnings yield turned negative. You may want to close one eye and use the other to look askance at the table because it's not pretty.

The Risk/Reward table shows just how limited the upside was.

The S&P failed to rally more than 7% at its best point within the next two years after all but one signal, from January 1980. That time, the S&P suffered a quick correction then rallied strongly in the year ahead (and then failed again). All the others showed maximum drawdowns of -32% or more. Ouch.

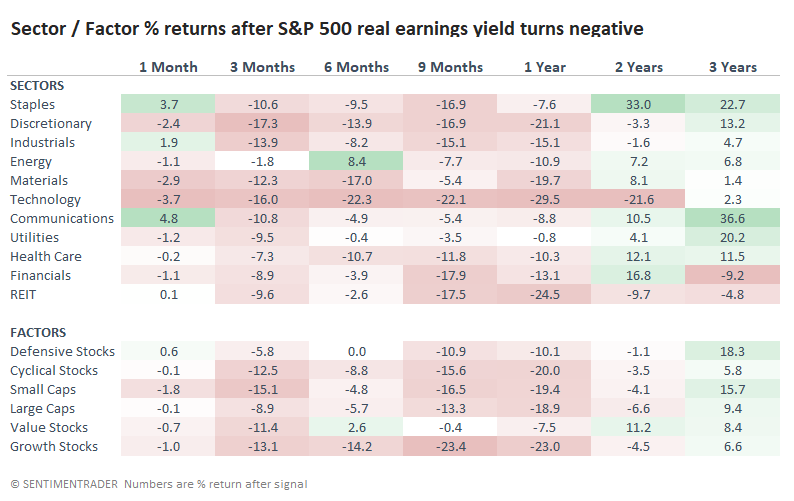

TECH TROUBLES, VALUE PREFERENCE

As Jay showed last week, inflation has had an especially pernicious effect on Technology stocks. And when we look at the average returns in sectors and factors following these same signals, the worst returns were, indeed, in Tech, Discretionary, and Growth stocks. There weren't exactly any winners, but the "best losers" included Value, Staples, Energy, and Utilities. Not a big surprise.

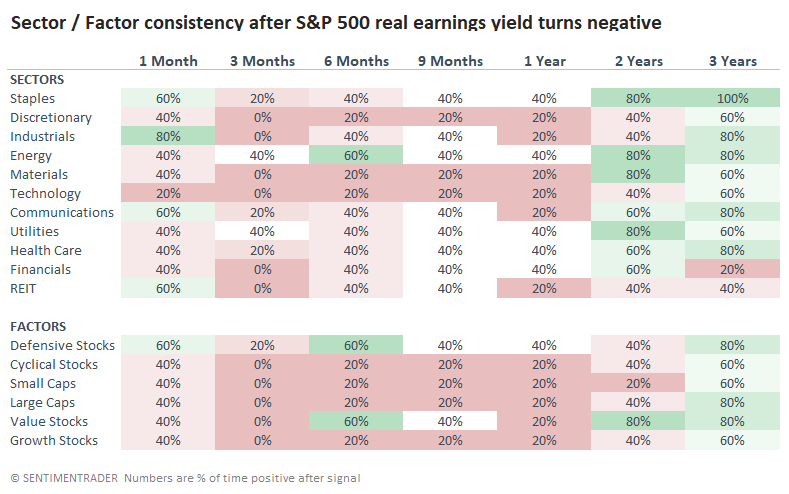

If we look at sector and factor consistency instead, it's a similar story. This is the percentage of time that each showed a positive return over the time frames. With a sample size of only five, it's not as informative as it would be with more precedents.

The biggest risk with putting weight on data like this is the this-time-is-different argument due to unprecedented stimulus, an unusually active central bank, and problems with measuring inflation, especially a base rate that's being so influenced by a once-in-a-century pandemic.

While acknowledging that history is never a perfect guide, we'd rather use it as a guide than pure guesses about why it's not valid. And this history is waving a major red flag for the long-term.