A breadth thrust that wasn't

Last week, stocks witnessed one of the most powerful three-day thrusts in history. Probably the most powerful.

There's always a "but," and this time the "but" is that it wasn't actually a breadth thrust. That's based on preconceived notions about what a thrust is. It's assuming there are rules when it comes to these kinds of signals.

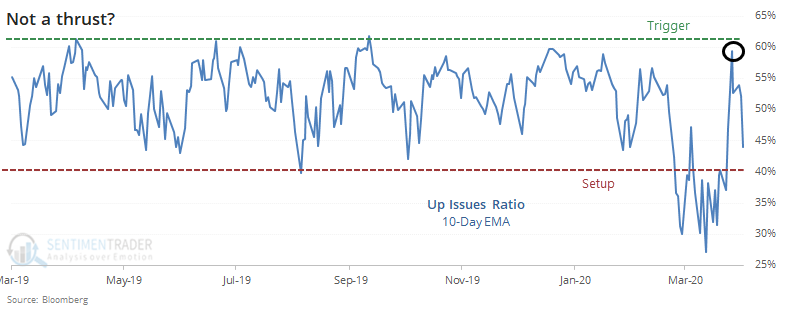

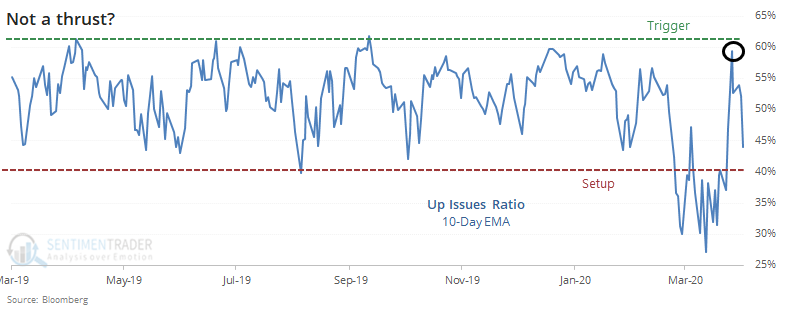

The most popular definition of a thrust is the one popularized by Marty Zweig, which looked for the 10-day exponential moving average of the Up Issues Ratio, which needs to cycle from below 40% to above 61.5% within 10 days. Because of a bad day on Friday, it didn't quite trigger.

The Zweig thresholds are considered gospel, but nothing like this should be. Why use Up Issues and not Up Volume? Why a 10-day average, and why exponential? Why a 10-day window? Why 40% and not 45%, and why does it have to exceed precisely 61.5%?

If a signal requires such specific criteria, then it's a big clue that it's not very robust. And that's one of the problems with using those criteria - the 61.5% threshold was picked because it excludes some dates which otherwise would have been failures.

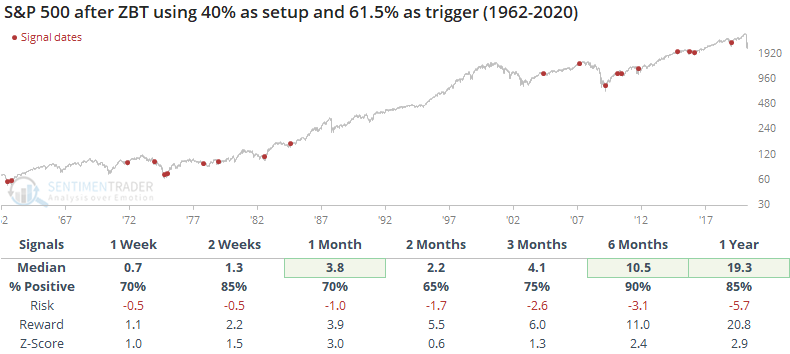

Using the original setup, returns were indeed impressive.

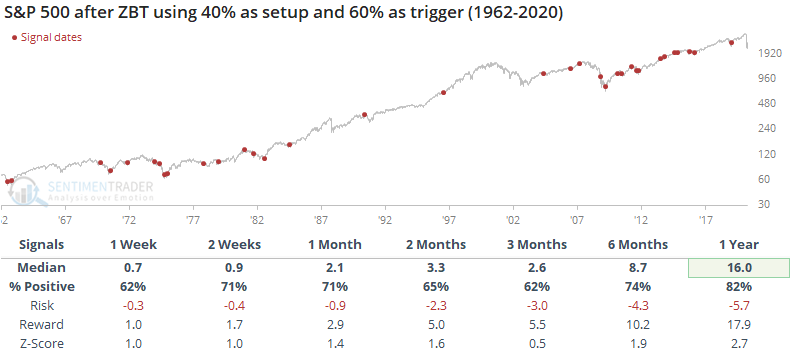

If we adjust the trigger to the round number of 60%, which would make a lot more sense, then the returns deteriorated.

Because of that one bad day, the ZBT didn't technically trigger. Let's see if it matters.

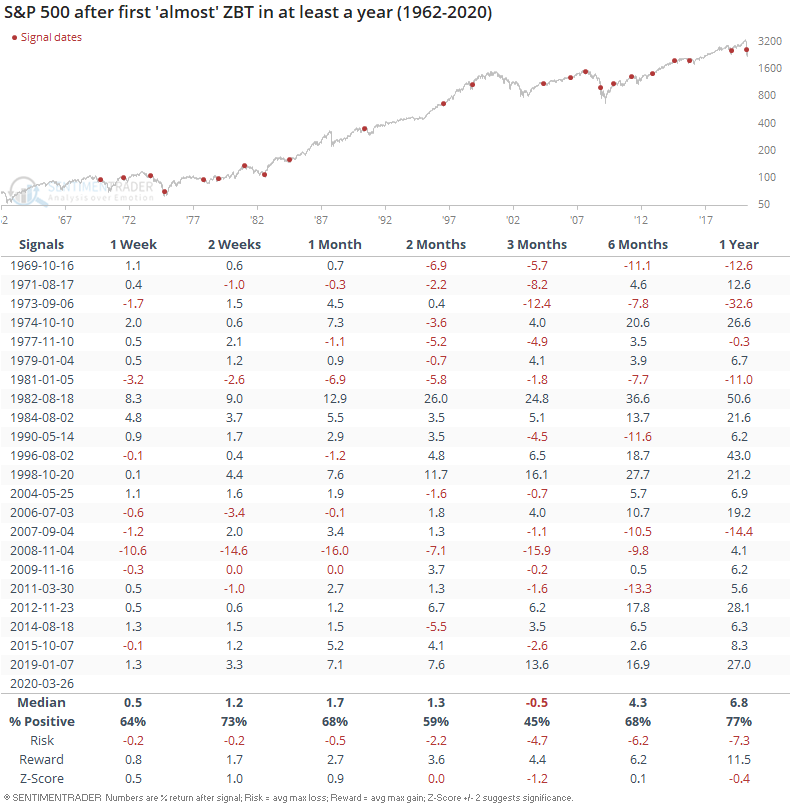

Below, we can see other times that we got an "almost" Zweig Breadth Thrust (ZBT). These are all the same criteria as the original signal, but the trigger is set to 59.3% instead of 61.5%.

Most of these led to good, but not great, returns. But this is ignoring a potentially important point - it's coming from one of the most severe oversold signals in history.

The setup requires the ratio to drop below 40%, but last month it plunged below 30%. If we look for "almost" thrusts that had a setup below 30%, then the table above would only include two precedents, the ones from August 2011 and January 2019.

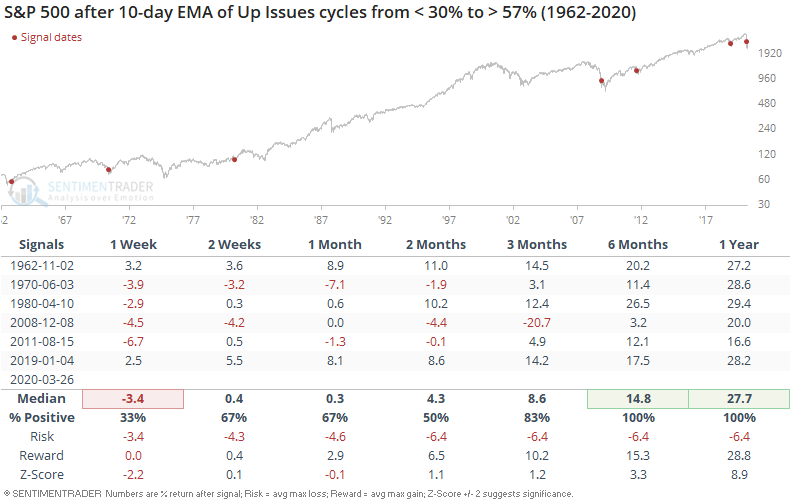

To expand the sample size, we'll lower the upper trigger threshold to only 57%.

Several of these preceded some wild swings over the next couple of weeks, and the one in December 2008 saw large losses over the next three months, but 6-12 months later they were all solidly positive, all marking important lows.

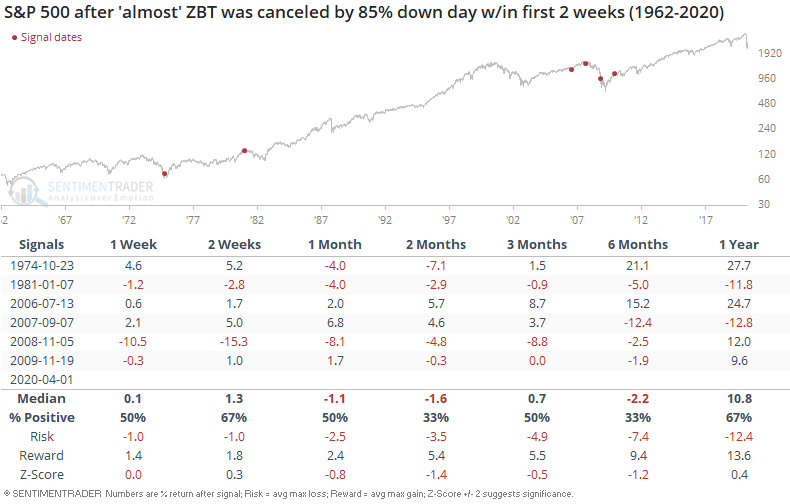

The concern now is that the weakness on Tuesday cancelled the signal. One of the guidelines is that there can't be a big down day within a certain number of days after the thrust. Using the criteria for the "almost" ZBT signals in the first table, below we see every time it triggered and then there was at least one day with 85% down issues within two weeks.

This didn't matter in 1974 (longer-term), 2006, 2007 (for a while), or 2009. It did in 1981 (when stocks were near a high) and 2008. Tough to read anything into all of that.

One of the dangers of looking at stats like this is that it's possible, even easy, to slice and dice them in a way that supports whatever view you want to show. That's why we spend a lot of time looking at different settings to make sure that signals are robust, and hopefully we communicate when they're not. Sometimes, the sample size is just too low and there's not much to do about that other than place less weight on the signal. It's also vitally important to consider the context in which the signals are triggering.

When we consider two facts:

- The past two weeks saw arguably the most oversold condition in 60 years, and

- Then we saw the most impressive 3-day thrust in history

Then the idea that it all doesn't count because a random indicator barely missed a cherry-picked threshold seems narrow-minded. There are definitely reasons to be concerned about this market, but the supposed lack of a breadth thrust is not one really one of them.