Surge in money growth does not have a consistent record

Economies are collapsing, governments are responding, and central banks are printing money. In the U.S. it has resulted in a massive increase in the money supply, which brings the usual chorus of commentary about this triggering inflation.

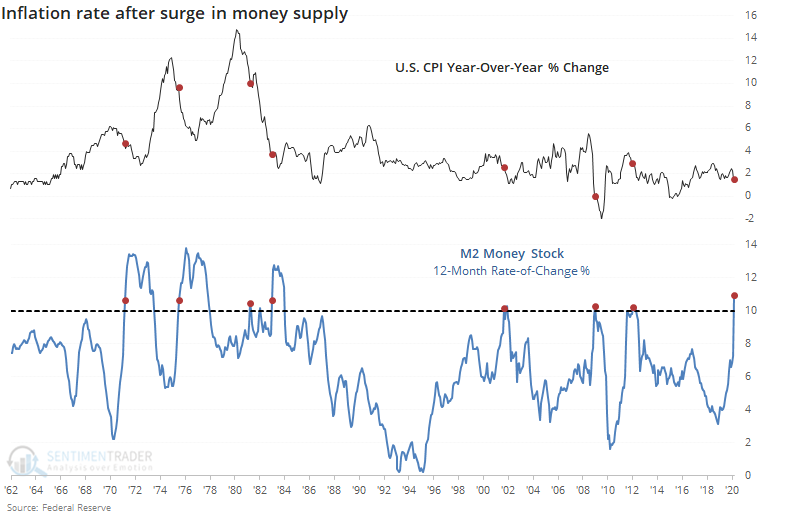

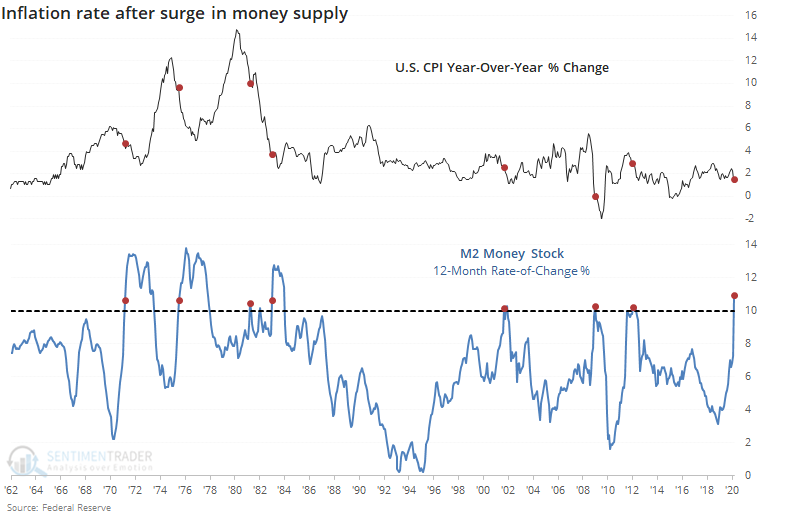

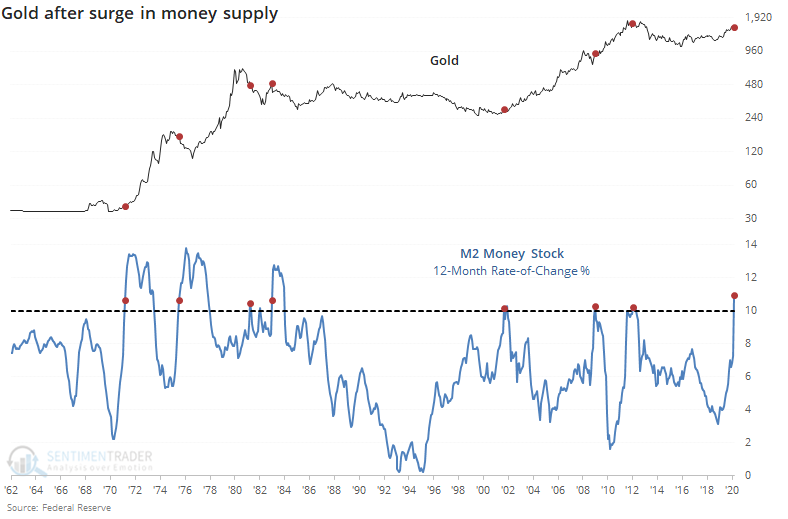

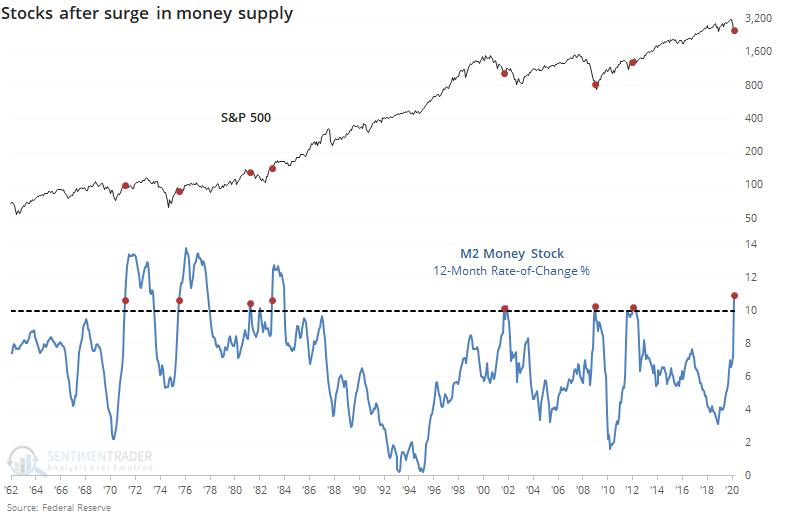

There is little point in adding another opinion to the chorus, so let's just look at the evidence, going back as far as we can. We'll compare times when M2 money supply rose at least 10% from a year ago, and see how that impacted inflation and various assets.

Per the St. Louis Fed:

"M2 includes a broader set of financial assets held principally by households. M2 consists of M1 plus: (1) savings deposits (which include money market deposit accounts, or MMDAs); (2) small-denomination time deposits (time deposits in amounts of less than $100,000); and (3) balances in retail money market mutual funds (MMMFs)."

For inflation itself, the argument that a rapid rise in money supply directly leads to a jump in inflation is a curious one because every single time, the rate of CPI growth decreased in the months ahead.

Usually, there is also an argument that it will lead to a surge in assets like gold. Here, the evidence is mixed, with a couple of them in the 2000s leading to rising gold prices, but most of the others leading to declines.

There was a similarly mixed picture for stocks. Some will argue it should be a negative, others a positive. The historical record shows about half of each.

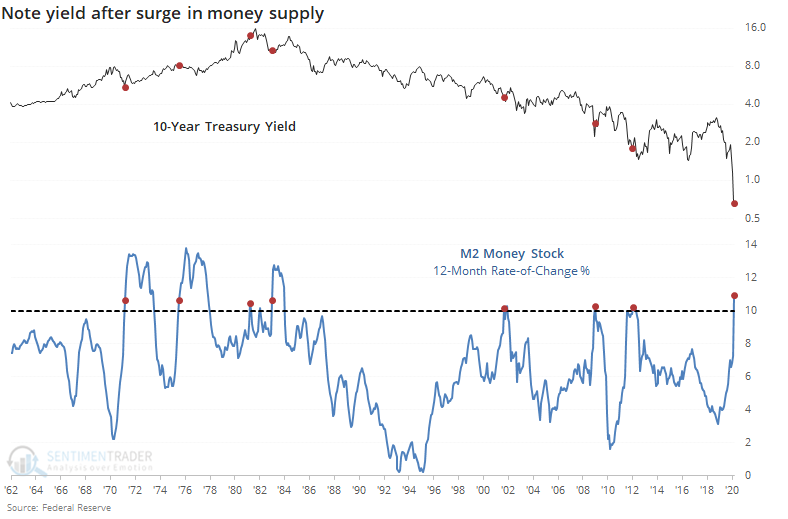

Most of these came during a time of ever-lower note and bond yields, but there was a modest bias toward a quick rise in yields at some point in the next year after these jumps in the money supply.

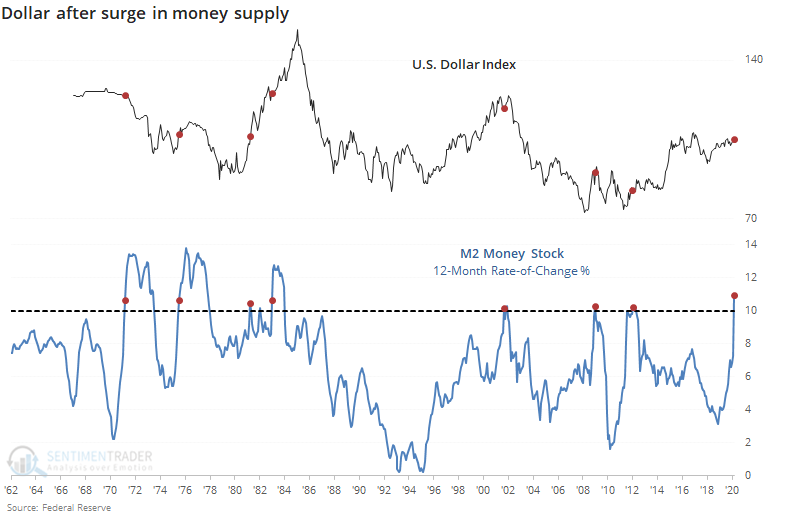

For the U.S. dollar, it's difficult to see any consistent bias.

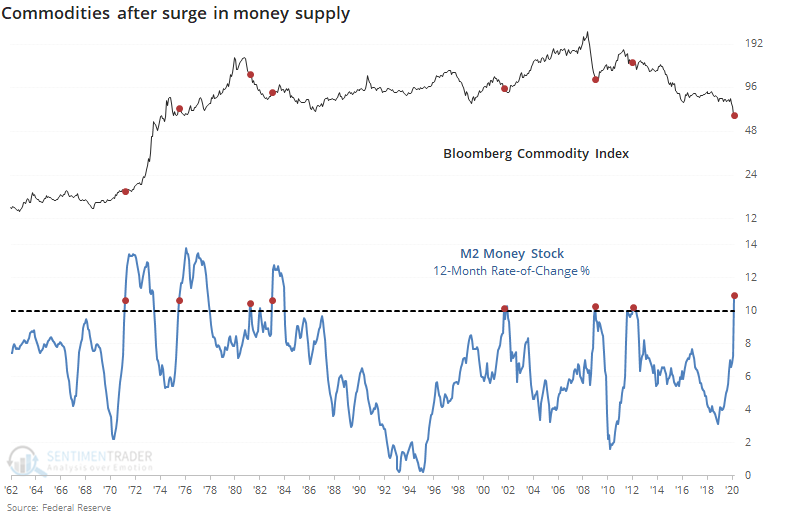

The same goes for the broader commodity market. There was mostly a positive bias to the Bloomberg Commodity Index after these signals, but in the early 1980s and again in 2012, commodities slid in the months ahead.

There are a lot of erudite suppositions out there about what this growth in money supply is going to mean, and they're worth considering. It's also worth considering that we have to rely on those opinions and selected historical precedents, because if we just rely on the data alone, then we can maybe say that inflation usually fell, while commodities and bond yields usually rose. Other than that, the record was mixed.