Secondary surge suggests companies are "feeding the ducks"

The economy is cratering, corporate outlooks are the most uncertain in generations, and yet stocks have rallied hard. That's a perfect recipe for companies to issue more shares. They get cheap capital in a friendly environment.

As Bloomberg notes:

“When you’re a CFO or a board director of a company in a capital intensive industry, you raise money so that you don’t lose your job. That’s 100% the right thing to do now.”

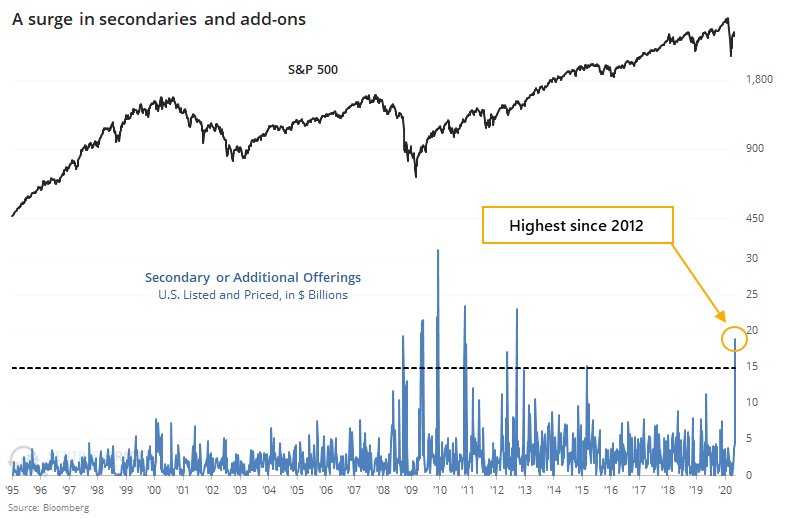

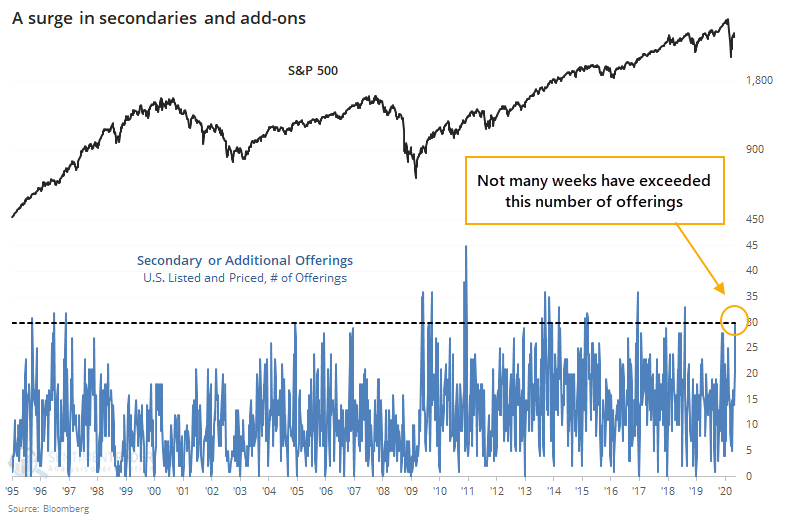

There is no doubt they're taking advantage and "feeding the ducks while they're quacking." This week alone, there has been nearly $20 billion of secondary or additional offerings priced among U.S. listed companies, and that's not including the full week yet.

When there is a jump in secondary or add-on offerings, it triggers a yellow flag among market watchers. It suggests that sentiment is perhaps too welcoming, in addition to the increased supply of shares.

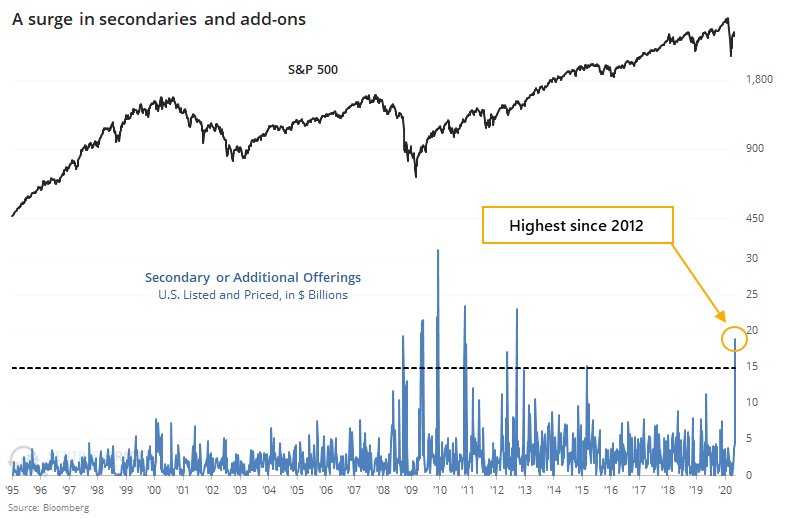

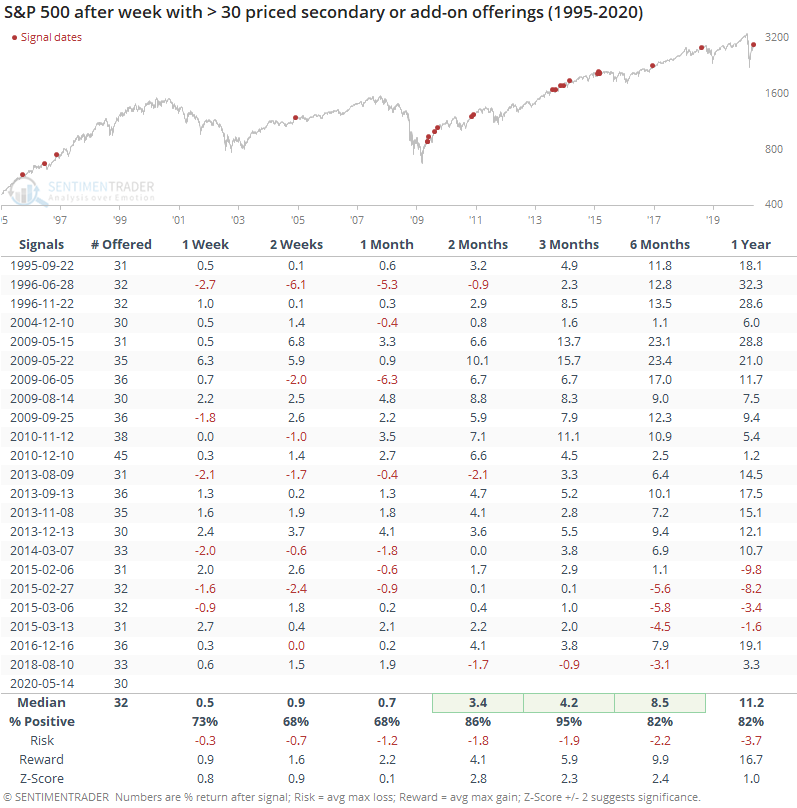

If we look at whether giant weekly spikes in these offerings led to poor market returns, that theory is hard to support. There was consistent weakness over the next couple of weeks, even though most of these occurred during a roaring bull market. But after that first couple of weeks, returns were good.

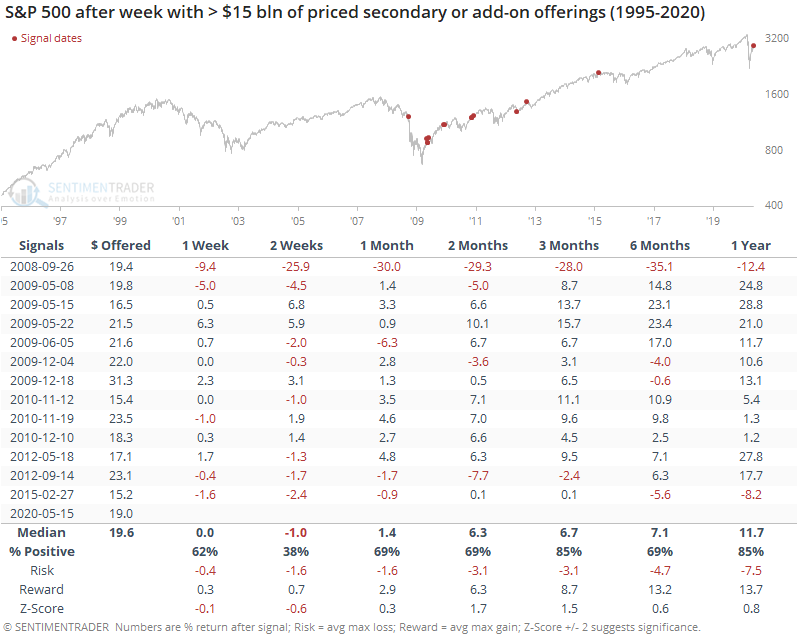

In terms of the number of offerings, it's been relatively spread out, so it's not one giant company that accounts for the big spike in the dollar amount.

When we look at the data this way, it's even less clear that this is a potential bearish catalyst. Returns over the medium-term were excellent, with rare losses.

This data can be variable depending on what criteria are used:

- Exactly what counts as an add-on?

- Do we include announced issues, or only those that were priced and trading?

- Is there a certain size of issue that qualifies?

- Is it only U.S.-based companies, or anything that's listed domestically?

- Over what time frame?

Because of those issues, other sources could come to different conclusions.

If we lengthen the time frame and look at monthly jumps in secondaries and add-ons, this month will like equal or exceed the summer of 2009 and late fall 2010, both times when markets were thawing after bouts of pessimism. Neither one proved to be negative indicators for the broader stock market's returns in the months ahead.

This is one of those things where a bearish argument makes a lot of sense, and it might be possible to torture the data in some way to make it confirm that suspicion. From the data we use, though, an objective look doesn't seem to support it as a negative influence at all.