A low short base just when markets need it most

The big topic over the past week has been short interest. By the sounds of mainstream media, there's a massive build-up of shares that greedy hedge funds have borrowed and sold, hoping to buy them back later at a lower price.

As usual, it's uninformed hyperbole. Short sellers provide an invaluable service to the investment world, and in any case, their thesis is completely wrong. In some stocks, there surely had been a huge build in the number of shares sold short. In the average stock, not so much.

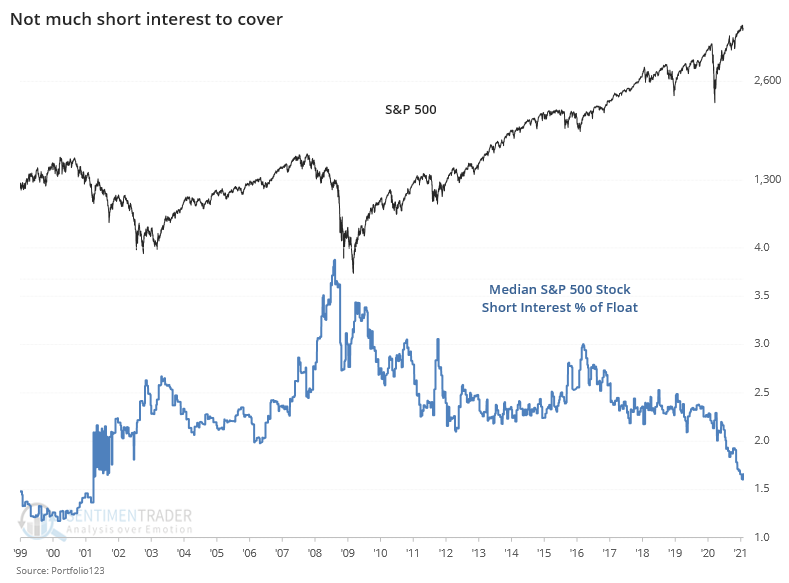

The median stock in the S&P 500 has only 1.6% of its float sold short, the lowest amount since 2001.

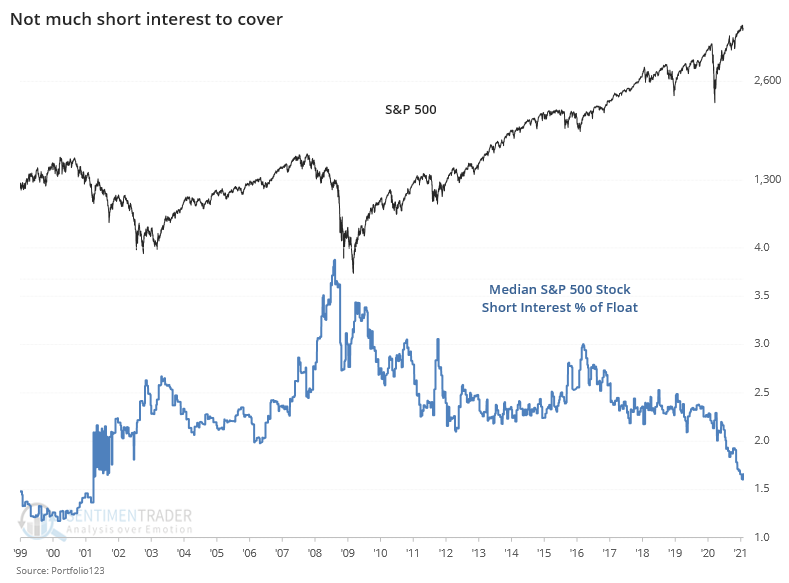

It's not just the large-caps in the S&P, though. The average stock across the S&P, Dow Industrials, Nasdaq 100, and Russell 2000 has just over 2% of its float sold short, a 17-year low.

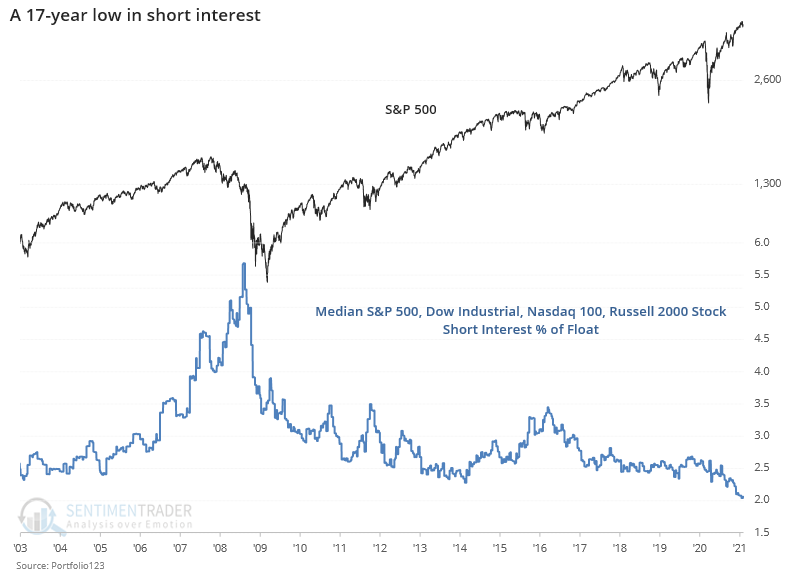

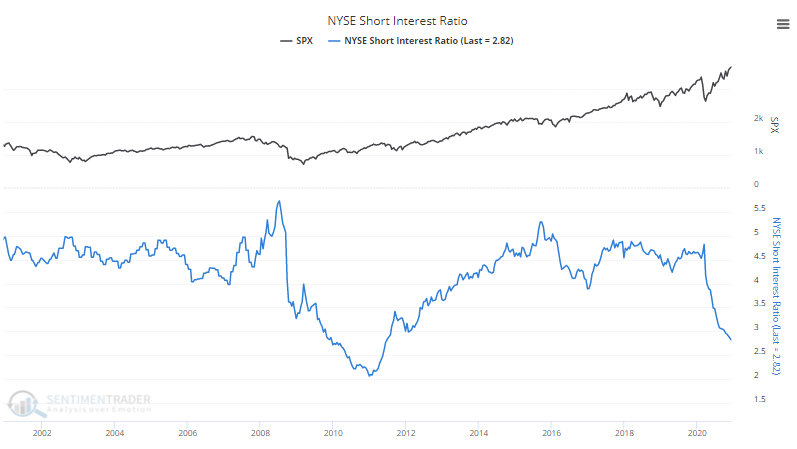

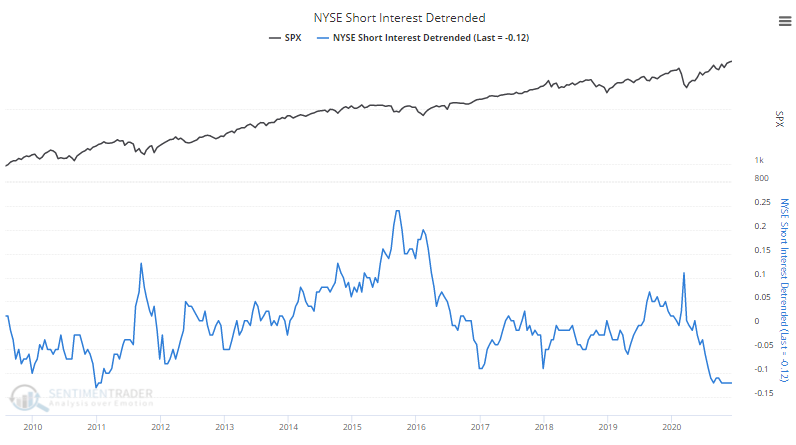

Across the broad NYSE universe, the Short Interest Ratio is near the lowest level in 20 years. Same for the Nasdaq exchange.

The De-Trended Short Interest Ratio is at its lowest level in a decade. This takes the current reading and compares it to its range over prior years, to give us a sense of relative extremes.

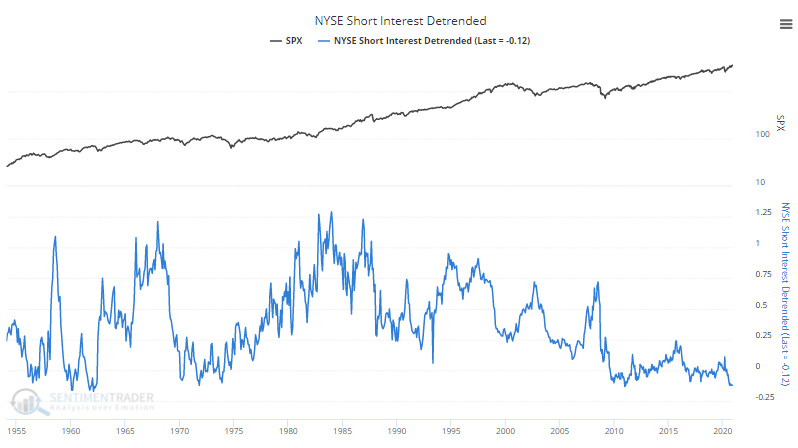

Even longer-term, it's nearing a record low.

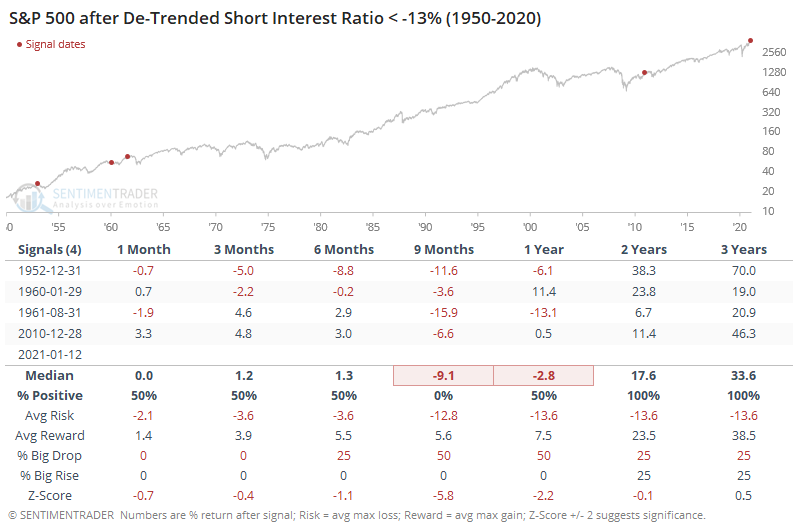

It's been this low only a few other times.

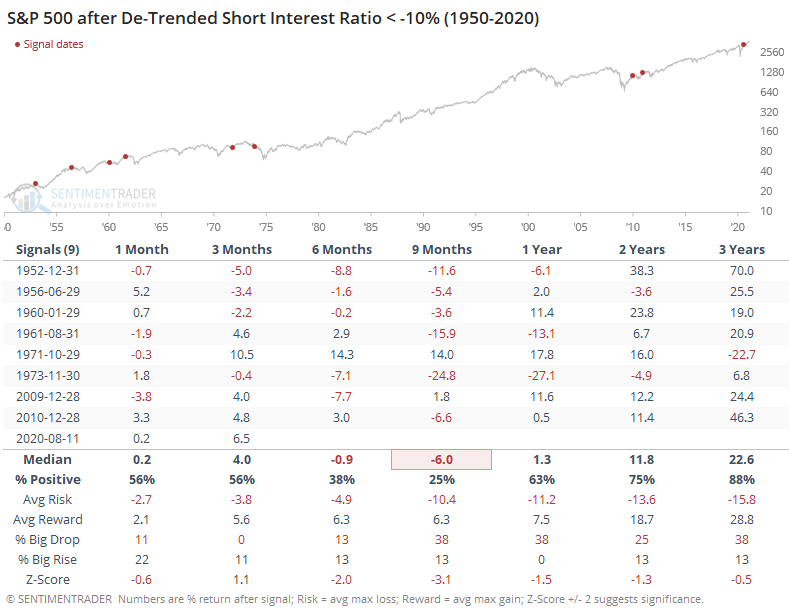

If we relax the parameters, then it triggered months ago, but prior instances tended to see muted returns up to 9 months later.

One of the main benefits of a healthy base of investors willing to sell short is that it helps to keep companies honest. Instead of the rah-rah "Great quarter, guys" from many analysts whose firms have investment banking relationships, shorts cast a skeptical eye and are willing to ask tougher questions.

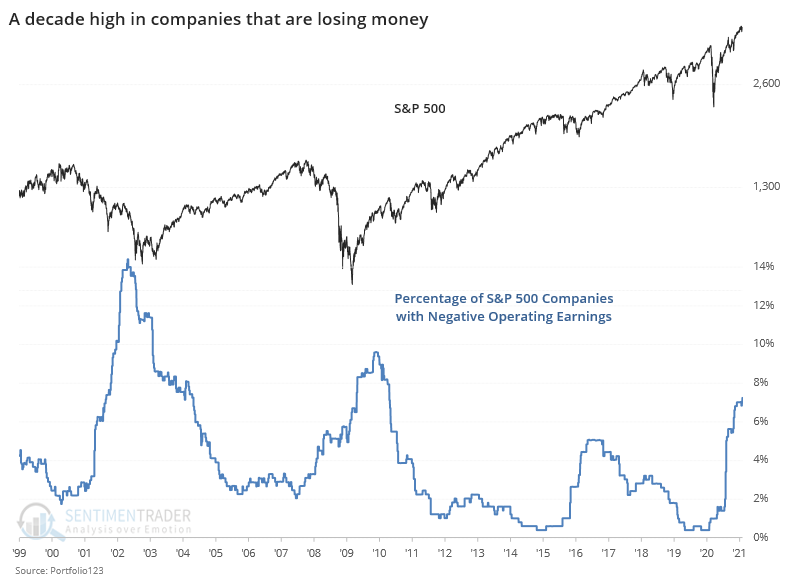

Perhaps it's never been more important. As companies emerge from the chaos of last spring, many of them are still losing money. More than 7% of firms within the S&P 500 are showing negative operating earnings over the past 12 months, the highest percentage in over a decade.

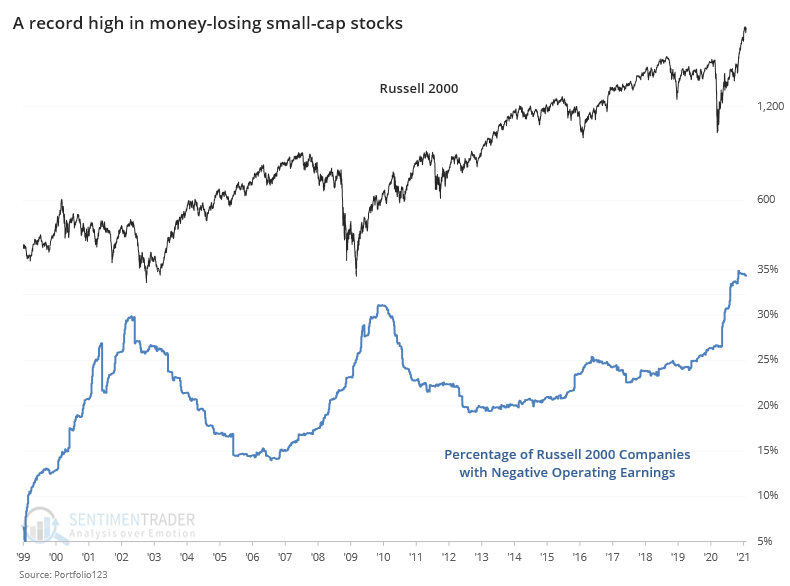

Again, it's not just those stocks. It's especially egregious in small-caps. Among companies in the Russell 2000, nearly 35% of them have not turned a profit, even as the index itself skyrocketed to one of its best rallies since its inception.

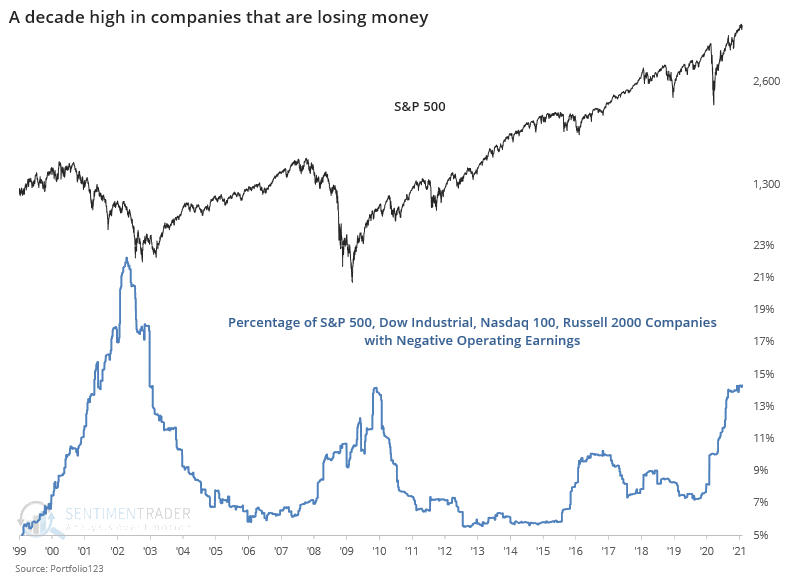

Across the S&P 500, Dow Industrials, Nasdaq 100, and Russell 2000, there is also a decade-high percentage in money-losing companies.

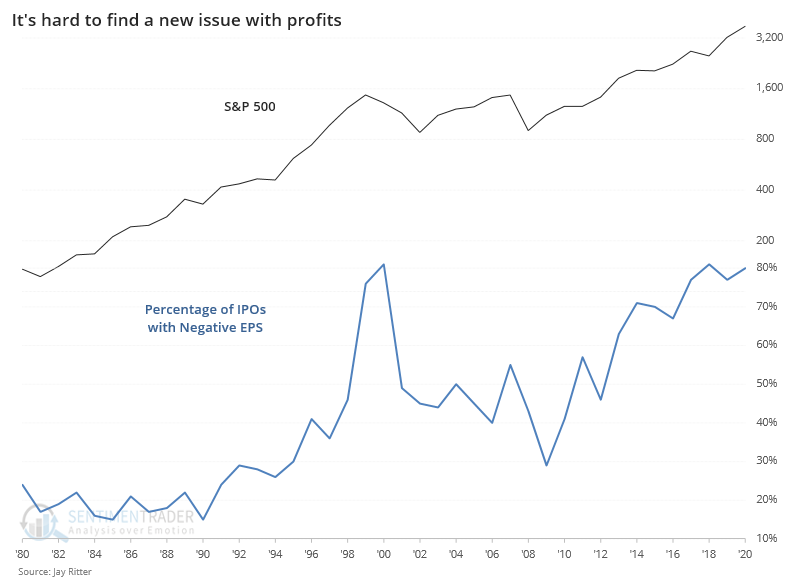

The worst offenders, of course, are the newest issues. We've discussed this repeatedly, and it bears mentioning again given the above. As of the end of 2020, about 80% of new issues did not turn a profit. Investors are willing to swallow a record amount of issuance, with the least discipline of possibly any time in history.

So, we have a situation with the most money-losing companies in a decade, with a market accepting of the lowest-quality issues ever, and a decades-low number of skeptical investors. This can go on for a while - at least weeks, possibly months, probably not years. Arguments could be made that history doesn't matter here given the fiscal/monetary environment. But it always seems like there's a regime change right around the time that the regime doesn't change.